LARRY H. LAYTON

RICHARD NARANJO

CRAIG RENETZKY

Monday, February 4, 2002

Page 5

Los Angeles Superior Court Office No. 39

Shadow of Antelope Municipal Court Lingers Over Superior Court Race

|

|

|

|

|

LARRY H. LAYTON |

RICHARD NARANJO |

CRAIG RENETZKY |

By ROBERT GREENE, Staff Writer

The Antelope Municipal Court in Lancaster was always a place apart, where lawyers in cowboy boots would feud or exchange local gossip in the courtroom without bothering to lower their voices and, if addressed from the bench, would often answer the judge by using his or her first name.

The place had its own culture and operated more like a small-town court than part of massive Los Angeles County. So when retirement time came for Judge Richard Spann, who was appointed to the Lancaster outpost in 1989, it stood to reason that there would be a couple of Antelope Valley lawyers running to succeed him.

Except that there is no more Antelope Municipal Court, nor has there been one for two years now. Spann was elevated in 2000 along with every other municipal court judge in the county to the Los Angeles Superior Court, and the vacancy left by his retirement will be filled by voters from Pomona to Pasadena to Palmdale to Palos Verdes.

There are seven such Superior Court judgeships on the March 5 ballot, and anyone elected to the court this year could find himself or herself sitting in any of more than 50 courthouses separated by hundreds of freeway miles.

But the notion of elections for discrete judicial posts apparently dies hard. In some respects, Superior Court Office No. 39 remains the Antelope Valley seat, with Acton law school dean and professor Larry H. Layton, Lancaster-based Deputy District Attorney Richard Naranjo, and prosecutor Craig Renetzky—whose assignments take him all over the county—vying for the post.

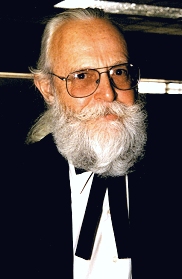

It is by no means the first run for Layton, 59, who ran unsuccessfully five times for the Antelope Municipal Court, most recently in 2000 against incumbent Pamela Rogers.

Layton’s bids have been low-key affairs, without fundraising or slate mailers. And this time out, countywide ballot statements run a steep $26,000 instead of the few thousand dollars they used to cost on the Municipal Court ballot. Layton says he does not expect to raise much more than the $2,400 he has already reported—and more than $1,300 of that went toward the filing fee.

So if such a campaign could not bring success in the more manageable confines of the Antelope Valley, how can he expect to mount a countywide campaign?

Actually, he says, he may have a better shot countywide, even though he can’t afford the ballot statement this time out.

“In the Antelope Valley the community is run by a very few people,” Layton asserts, naming his ex-opponent Rogers, attorney R. Rex Parris, and state Assemblyman George Runner and his wife, political consultant Sharon Runner. If a candidate is not close with those movers and shakers—and Layton states plainly that he is not—he is fighting an uphill battle.

The theory goes that in the countywide race, where no one has the clout of a local machine, none of the candidates paid for ballot statements and all appear before voters as just names and occupations, Layton has a chance.

Ballot Designation

The ballot designation, law school professor, refers to one of Layton’s roles at the Larry H. Layton School of Law in Acton, which he owns and operates. He says he believes the wording will stack up favorably against the two prosecutors, but he expresses dismay that voters must rely on ballot designations and slate mailers for information about the candidates.

Even if he had a lot of money to spend, he says, “I’d have to really consider if I wanted to spend it on a slate mailer.”

“I think the slate mailers [are] a tragedy,” Layton says. “Every slate mailer has some sort of agenda.”

Instead, in this county of 12 million people, Layton says he is relying on word of mouth.

With his double-string Western tie, his white hair and his ample white beard, Layton comes across as a colorful character, perhaps a cross between Colonel Sanders and Santa Claus. An actor, he has played Kris Kringle in stage productions of Miracle on 34th Street.

But where Santa might be ample and jolly, Layton is slender and soft spoken.

He is a former missionary, and in past campaigns has listed himself on the ballot as “attorney/evangelist.” But not this time.

“I’m just as fair with people if they don’t have any religion,” he explains, adding:

“I’m trying to keep an image that is true to my character. That I’m fair and just. I’m just trying to get across the point that I’ll be fair.”

Course Summaries

Layton grew up in Sylmar and attended high school in San Fernando. In 1972, while a student at Glendale College of Law, he prepared and sold course summaries and soon launched a business distributing materials that prepared first-year students at non-accredited law schools for the so-called baby bar exam.

Becoming a member of the bar in 1975, he practiced in the San Fernando Valley and served as a judge pro tem in the Van Nuys and San Fernando courthouses, sometimes handing out evangelical materials from a sidewalk stand across the street.

Meanwhile he launched the short-lived United States School of Law in Panorama City, then taught at the California College of Law.

He relocated to the Antelope Valley in 1987.

Today, he runs his own law school, with a student population this year of seven. Classes are held on Friday nights and Saturdays. He boasts that all of his students who take the bar exam pass it, and that his is the only family-owned law school in the nation.

He still handles some cases and says he’s in court three or four times a year.

He is the best man for the job, he says, because of his many years of experience.

“I have not only practiced [law] but I have been teaching many subjects,” he says.

Third Career

Law is a third career for Richard Naranjo, 49, a Long Island native who went to Rutgers in New Jersey on a scholarship and played football and ran track. A broken leg in 1974 ended his college career, and he went home to where his father had moved—New Hampshire.

There, he worked in finance and banking and for his father and then a series of other companies in production and inventory control. Meanwhile, on what Naranjo calls the “17-year plan,” he earned his degree from New Hampshire Technical College and met the woman who was to become his wife, Wendy Naranjo.

It was his wife, he said, who first got the inspiration to go to law school after receiving a jury summons. Naranjo took that as a challenge, and they both applied. He ended up at Southwestern University School of Law in Los Angeles, she at Loyola Law School.

In the move west, he changed his name—sort of. He would answer New Englanders who asked about his name by sounding out, Nar-An-Joe. In California, where Spanish names are common, he became Nar-An-Hoe.

During his last year at Southwestern, Naranjo took an internship at the District Attorney’s Office, and he stayed on after graduation. After a few assignments around the county he landed in Lancaster, where he has served for eight years.

The Antelope Valley assignment is luck of the draw, and Naranjo can no more take credit for it than can his opponent, Renetzky, for his assignment to a task force that has sent him around the county.

But Naranjo, who lives in the Santa Clarita Valley, says he enjoys working in Lancaster and would be pleased to work there as a judge, especially in the juvenile delinquency court.

In appearance, Naranjo fits the television profile of a prosecutor—tall, stern, businesslike. He says that as a prosecutor he is even-tempered, but that he has been known to attack if attacked by opposing counsel.

He says that as a judge he would place a high premium on courtroom decorum, starting with his own conduct on the bench.

“As a judge, you can’t afford to go off” even if provoked, he says.

“I’d like to do my little part to get the esteem back” into the courtroom, he says.

1996 Bankruptcy

Naranjo has a 1996 Chapter Seven bankruptcy on his record, a product of what he says was a crisis in his wife’s pregnancy. Wendy Naranjo’s medical condition was so severe, her husband explains, that she had to quit her job doing legal research and confine herself to bed-rest. The income was gone, but the student loan and other bills kept coming.

“It got to the point where people were calling at all hours of the day and night threatening legal action,” Richard Naranjo says. “We were fighting constantly.”

They chose bankruptcy, he says, to preserve the marriage and the family.

He says the couple have followed a reduced payment schedule, although most of the debts were not discharged.

“We are meeting our commitments,” he says. “It’s very embarrassing that this happened. But it should affect a voter’s decision. The voter should see that this is a person that chose to preserve marriage and family.”

Wendy Naranjo ultimately gave birth to healthy twins. They are the couple’s fourth and fifth children.

Naranjo is running what appears, in essence, to be an Antelope Municipal Court campaign. Like his opponents, he has opted against a costly ballot statement, and he plans to use the money he does raise on signs in the area.

If possible, he adds, he will send out mailers with the message that, with his decade as a deputy district attorney and his prior work in business, he is the most qualified to sit on the court.

He says he won’t be raising tens of thousands of dollars.

“If I can get 10 grand...I’d be very happy,” he says.

Minimum Requirement

Craig Renetzky, 34, also has served as a deputy district attorney since 1991, starting with the office in the same class as Naranjo. The two men both have just over the bare minimum 10-year requirement of law practice to become a judge.

But while Naranjo was sent to Lancaster for most of that time, Renetzky was assigned to the Community Oriented Multi-Agency Narcotic Enforcement Team, a task force that keeps him moving to courthouses all over the county.

And that movement, Renetzky says, is what sets him apart from his two Antelope Valley-based opponents.

“I’ve really seen the county,” he says. “I’ve had the opportunity to see hundreds of judges and hundreds of courtrooms.”

Renetzky says that experience has taught him what people in various communities expect from their courts.

If appearance were to play a role in the election, with Layton playing the character and Naranjo the prosecutor out of central casting, Renetzky would be the kid. He appears even younger than his age, and speaks about his campaign with the excitement of a youngster on an adventure.

“The filing deadline was Dec. 7, so you didn’t know who you were running against, and you can’t do much fundraising during Christmas, and endorsement groups meet monthly and they often don’t meet in December, so there’s a lot to do all at once,” Renetzky says. “And the election is in March. Rather than like a marathon it’s more like a sprint.”

Boyish Enthusiasm

But although Renetzky may speak with a certain boyish enthusiasm, he is married and the father of two children, ages 8 and 6. Besides, appearance generally means little in a countywide judicial race, and on paper Renetzky can display the high regard of a number of judges and elected officials. His endorsements include Superior Court Judges Norm Shapiro, Lance Ito, Larry Fidler, Jacob Adajian and Maral Injejikian.

He has also garnered the backing of law enforcement groups of the type that generally make voters sit up and take notice: the Los Angeles County Professional Peace Officers Association, Citizens for Law and Order, the Hispanic American Police Command Officers Association.

A Tarzana resident, Renetzky grew up in the San Fernando Valley, then went to college at Colorado College in Colorado Springs. He then attended USC Law School and like Naranjo, interned at the District Attorney’s Office. He has never left.

Alone among the three candidates, Renetzky has hired a political consultant. Fred Huebscher has steered several other candidates to judicial victory and he is representing a number of candidates in the current campaign, including Renetzky’s father, Workers’ Compensation Judge Donald Renetzky.

Craig Renetzky says it sounded to the two of them like fun to both run for judge at the same time, although their campaigns are separate. His own campaign, he says, is likely to last to November.

“Whenever you have two prosecutors in a race there is a good chance of a runoff,” he explains.

He calls Naranjo a “nice guy” but would distinguish himself based on his wider experience, in more courtrooms and before more judges.

If he draws an assignment in an area other than felonies, he acknowledges that he will have some catching up to do. But he says the same is true of anybody.

“I fully admit that if you throw a civil case my way I’m going to be spending a lot of hours learning the law,” Renetzky says. “You learn.”

Renetzky says he does not plan to raise a fortune to get elected. But he adds that he will put $5,000 of his own money into the campaign and expects to have a warchest for the runoff—if there is one.

Copyright 2002, Metropolitan News Company