Page 3

Ninth Circuit:

Website’s Wording Insufficient to Infer Consent to Arbitration

By Kimber Cooley, associate editor

|

|

|

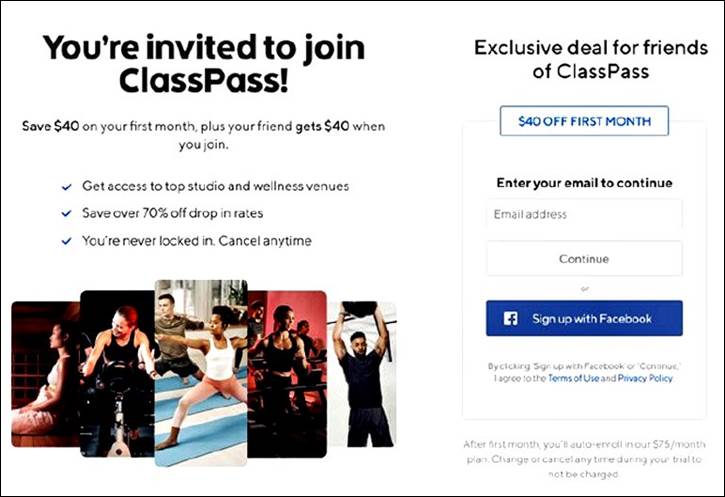

Above is a screenshot from a webpage which the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals said yesterday, in a 2-1 opinion, does not provide adequate notice that a user is agreeing to arbitrate any disputes. |

The Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals held yesterday, in a 2-1 decision, that a website offering packaged deals for access to fitness classes and studios failed to bind users to an agreement to arbitrate claims where scroll-through pages displayed a “Terms of Use” hyperlink leading to the contract but no effort was made to ensure that the document was read.

Finding that the website most closely resembles a “sign-in wrap” agreement—which is enforceable under governing jurisprudence if the website provides reasonably conspicuous notice of its terms and conditions and the consumer takes some action, such as clicking a control or checking a box, that unambiguously manifests assent—the court took issue with the fact that the available buttons only said “Continue” or “Redeem now.”

Circuit Judge Salvador Mendoza Jr. authored the opinion for the divided court, saying:

“Like many wishful thinkers, Katherine Chabolla started off 2020 by resolving to improve her fitness and wellness. So that January, she went online and purchased a trial subscription with ClassPass….But March brought with it a global pandemic, and California’s gyms and studios closed their doors. ClassPass did not charge Chabolla’s account for months, but when operations resumed so did ClassPass’s charges. Chabolla sued, alleging the resumed charges violated California law. ClassPass argues that when Chabolla used its website, she agreed to arbitrate any claims against it.”

He continued:

“We are presented with a question of ever-increasing ubiquity in today’s e-commerce world: whether an internet user’s online activities bound her to certain terms and conditions. We do not know if Chabolla’s New Year’s resolution survived 2020. But as to her claim in federal court, we hold that it survives ClassPass’s motion to compel arbitration….”

District Court Judge Michael Fitzgerald of the Central District of California, sitting by designation, joined in Mendoza’s opinion. Senior Circuit Judge Jay S. Bybee dissented.

Subscription Service

After ClassPass resumed charging Chabolla in 2021, the plaintiff filed a class action complaint against it, and certain related entities, asserting claims under California’s Automatic Renewal Law, Unfair Competition Law, and Consumers Legal Remedies Act.

ClassPass filed a motion to compel arbitration, pointing to an agreement in the company’s “Terms of Use” which was available, via a blue hyperlink, on the company’s website, where a landing page provided options for purchase and a user was directed to click through to subsequent pages.

The first screen provided that “By clicking ‘Sign up with Facebook’ or ‘Continue,’ I agree to the Terms of Use,”

but the advisement, and hyperlink to the provisions, were in the smallest font on the page and set off to the side from the rest of the information. Chabolla clicked “Continue” and did not utilize the “Sign up with Facebook” option.

On the second page, fill-in boxes were provided for a consumer to enter her name and directly underneath—in the same small font as on the first screen—were the words “By signing up you agree to our Terms of Use” and a button marked “Continue.”

A third screen was a checkout page and contained the following statement, in the same-sized lettering:

“I understand that my membership will automatically renew to the [$79] per month plan plus applicable tax until I cancel. I agree to the Terms of Use….”

A “Redeem now” button was found directly beneath the acknowledgement, which Chabolla clicked.

District Court Judge Yvonne Gonzalez Rogers of the Northern District of California denied the motion to compel based on the arbitration agreement found in the terms and conditions. Yesterday’s opinion affirms the order.

Visual Aspects

Mendoza considered the visual aspects of the website and found that the notice on the first screen failed “[b]ecause of [its] distance from relevant action items, its placement outside of the user’s natural flow, and its font—notably timid in both size and color.” Under those circumstances, he declared “any action the user takes on the page cannot unambiguously manifest her assent to those terms.”

Turning to the notices provided on the other pages, he noted that “screens 2 and 3 place the notice of the Terms of Use more centrally” but said that “[w]e decline to consider any further whether [these] notices…are conspicuous enough” because “a user must agree to the terms, not merely see them.”

Addressing assent, he remarked that “[a]t no point on any screen is a user advised that a particular action has ‘signed her up’ or will ‘sign her up,’ ” and said:

“Rather than provide explicit instruction….[i]t is up to the user to assume that entering a first and last name and clicking the…button amounts to ‘signing up.’ We find too much ambiguity in [the] language to find that a user binds herself to the Terms of Use….”

ClassPass urges that its “webflow” is a “multi-page enrollment process” and that “[a]ny reasonable Internet user would understand what she was doing.” Rejecting the contention that the scroll-through process, taken as a whole, provided sufficient notice of the terms and indication of consumer consent, Mendoza declared:

“Viewed in total, we do not think a reasonably prudent internet user unambiguously manifests assent to the Terms of Use by working her way through ClassPass’s multi-page website.”

Bybee’s View

Bybee wrote:

“I would hold that the ClassPass screens, considered individually or jointly, satisfied the ‘reasonably conspicuous notice’ requirement. I am confused by the majority opinion on this prong. The majority questions whether ClassPass’s Screen #1 satisfies the ‘reasonably conspicuous prong,’ and then waffles as to whether Screens #2 or #3 individually (or considered together) satisfy it.”

As to whether there is an unambiguous manifestation of consent to the terms, he said:

“Screen #1 does exactly what [case law] says is enough. It states that ‘By clicking “Sign up with Facebook” or “Continue,” I agree to the Terms of Use….’ ”

He argued that while “the language could have been clearer” on the next two pages, Chabolla was provided with “easy access” to the terms of use as she continued with the sign-up process and said that “in context it was clear what she was doing when she clicked” the “Redeem now” button.

Under those circumstances, he commented:

“The screens, considered individually, required Chabolla to manifest her assent to the Terms of Use. When we consider all three screens together, that conclusion is not only inevitable but overwhelming. Chabolla received three conspicuous notices of the Terms and unambiguously assented three times during the sign-up process. For any reasonably prudent Internet user, this was enough to bind her in contract.”

No Minor Dispute

The jurist continued:

“If this were just about Chabolla—if this were just a minor dispute about the vagaries of language—I might not be so concerned to put this all in writing. But I fear the effects of the majority’s opinion extend far beyond this case. The majority’s decision demonstrates that we will examine all internet contracts with the strictest scrutiny and that minor differences between websites will yield opposite results. A website such as ClassPass cannot rely on our [past] decisions…, which approve nearly identical language. That sows great uncertainty in this area.”

He added:

“When companies structure their websites to respond to our opinions but can’t predict how we are going to react from one case to another, we destabilize law and business. After today’s decision, a website will have to guess whether any nuance at all in its sign-in wrap will be held against it. The result is one of caveat websitus internetus (roughly translated as ‘internet websites beware!’)”

The case is Chabolla v. ClassPass Inc., 23-15999.

Copyright 2025, Metropolitan News Company