Special Section

PERSONALITY PROFILE:

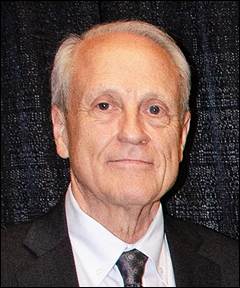

ROBERT GREENE

He’s a Lawyer With a Pulitzer Prize Tucked Under His Arm

By Sherri Okamoto

American poet Emily Dickenson once reflected, “I know nothing in the world that has as much power as a word.” When wielded by a wordsmith with the skill of Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist and attorney Robert Greene, the full power of the written word is clear.

He’s shy and soft spoken—but a master of effective advocacy. When he puts a pen to paper, there’s no ignoring what he has to say.

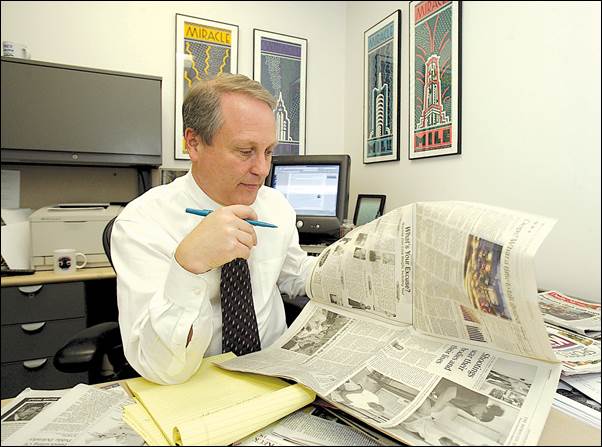

With a background as a practicing lawyer in what was then a major firm in Los Angeles—Lawler, Felix & Hall, no longer in existence—he joined the MetNews as a staff writer, advancing to the post of associate editor. He reported on appellate cases that were just handed down and intensively covered city charter reform and the 2000 unification of the county’s trial courts.

Too, he authored pithy, witty, sometimes playful columns for the Metropolitan News Company’s weekly newspaper, the Civic Center NEWSource, now demised, displaying a style distinctively his, one that was to mark a legion of editorials he crafted for the Los Angeles Times.

Greene attained the post of editorial writer for the state’s foremost newspaper after an intermediate hitch with an alternative-press weekly. It was based on his writings in the Times on criminal justice issues—unbylined, as editorials traditionally are—that he received the highest honor any journalist (or persons in various other fields) could possibly attain: the Pulitzer Prize.

Esteemed by colleagues at the Times, and seemingly destined to remain at his post until retirement, Greene abruptly departed from the newspaper in October. That was in protest to the decision by the owner, Patrick Soon-Shiong, not to accede to the editorial board’s resolve that Democratic nominee Kamala Harris be endorsed for president of the United States in the general election. Greene said, in his letter of resignation:

“I recognize that it is the owner’s decision to make. But it hurt particularly because one of the candidates, Donald Trump, has demonstrated such hostility to principles that are central to journalism—respect for the truth and reverence for democracy.”

As the result of his stance, Greene, who for decades covered news, himself became a subject of news reports, ones published and broadcast internationally.

Cooley Comments

Based on his rare—if not singular—status as a Los Angeles lawyer vested with a Pulitzer Prize, as well as his highly principled nature, Greene will be honored, along with five others, at the Jan. 31 MetNews “Persons of the Year” dinner. Emceeing it will be former Los Angeles County District Attorney Steve Cooley, who mentions that he’s known Greene for about as long as he’s been a public figure and Greene has been a journalist.

Cooley, a political conservative, says in paying tribute to the espouser of liberal viewpoints:

“I’ve held great admiration for him in all of his various roles as a journalist from his time at the LA Weekly and the MetNews and his long stint at the Los Angeles Times. Suffice it to say Robert and I are not of the same political bent, but we enjoy each other’s company, and I can say without hesitation we need more Rob Greenes in the world.

“By that I mean skilled journalists who can express an opinion on issues of great concern to the public at large.”

Lawyer’s Son

Greene was born in San Francisco, the second child of Marvin and Revlyn Greene. His family moved to Los Angeles when he was an infant. It was here that his father, an attorney, went to work for Gendel, Raskoff, Shapiro & Quittner (a firm that no longer exists), and then the venerable Loeb & Loeb.

|

|

|

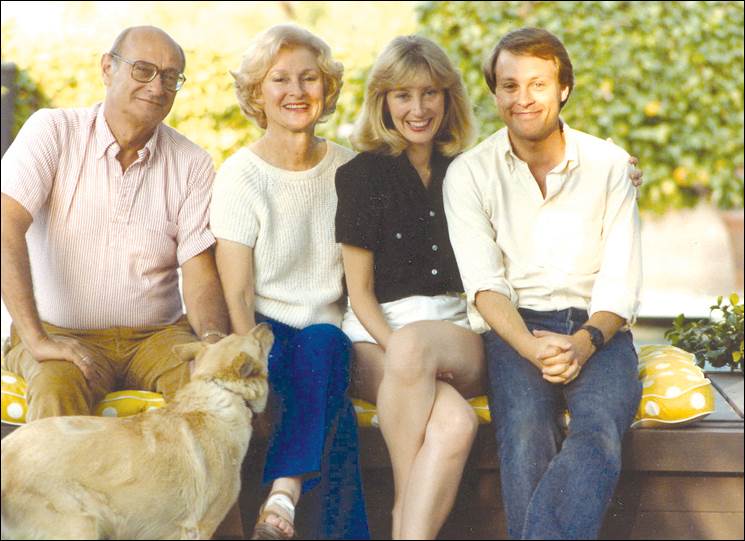

Depicted are Greene’s father Marvin, mother Revlyn, sister Andi, and Greene posing for a family photo in their backyard. |

After his father passed away in 2004, Greene says, his mother told him, “Your father had really wanted to be a journalist.” That was news to Greene, who says that when he was growing up, he thought his father had wanted him to be a lawyer.

A nose for news must run in the family though, as Greene’s older sister grew up to be a television news reporter and then a spokesperson for LA Metro.

As a child, Greene says, he “always liked the idea of writing for a living,” but adds:

“That didn’t mean I was any good at it.”

Krinsky Comments

Miriam Krinsky, a former president of the Los Angeles County Bar Association and a former federal prosecutor, says that Greene hasn’t changed much from when they met at Hale Junior High School in Woodland Hills.

“He’s an exceptional individual with an incredible curiosity and intense depth of thought,” Krinsky says of her longtime friend. “Rob was that way from a young age.”

She jokes that her first exposure to politics was through Greene, helping him paint signs when he ran for student body president.

“He won, not surprisingly,” Krinsky remarks. “He was a natural leader.”

Greene “has always been incredibly well-liked because he doesn’t have a huge ego” and “that’s not always something you see in wonderfully talented and accomplished individuals,” Krinsky observes. “He was never one to toot his own horn.”

While Greene generally is “not the loudest voice in the room” Krinsky says that “he’s probably one of the most thoughtful voices in the room.” He “isn’t showy about what he brings,” she continues, but Greene is always striving “to enlighten others, to find a way forward, and to understand complex issues.”

She adds that she probably would not have become a lawyer had it not been for Greene and his father. When she was a child, Greene’s father had brought her into his firm office and introduced her to the one female partner, to show her what was possible, Krinsky recalls.

Greene’s mother is also remarkably well-read and well-spoken, so “the apple did not fall far from the tree,” Krinsky opines, with reference to both parents.

“He’s someone with a good heart and a passion for trying to leave the world a better place,” which makes sense considering he had “the most lovely, warm, caring individuals as role models,” she says.

Became a Trojan

After graduating from El Camino Real High School in 1977, Greene went to the University of Southern California. He lived on campus even though his family home in Woodland Hills was less than an hour away. Greene says he “wasn’t ready to go across the country” at 18, and while he wanted the “college experience,” he also wanted to be able to go home every other weekend or so.

Greene majored in English and “got really into studying English literature.” His developing fascination with the great literary works from the United Kingdom may not have done wonders for his social life, but he would spend “hours and days on end in the library reading beyond what was assigned for class.”

As his college graduation drew near, Greene says, something dawned on him:

“I realized my degree qualified me to speak English, which I already knew how to do.”

But, he thought, that would not aid him, career-wise.

“I needed to find something to do,” Greene says, and he reflected that “I liked the life that my father had,” elaborating:

“I liked that his friends and acquaintances were smart and intellectual, I liked that he made a good living, and I thought, well perhaps becoming a lawyer is the best way to achieve those things.”

While applying to law school was the byproduct of the fact that Greene “wasn’t sure what else to do,” at least he knew where he wanted to go.

Trip to Washington

When he had been a young teenager, about 12 or 13, he accompanied his father on a business trip to Washington, D.C.

“I was fascinated by that trip,” Greene recalls.

They went to monuments, museums, and the Capitol—but the highlight for Greene was the campus of Georgetown University.

“I fell in love with it,” Greene says, “and I decided I wanted to go there.”

With his four years at USC behind him, Greene was ready to move across the nation and he applied to Georgetown University Law Center —despite knowing the law school wasn’t even on the main campus.

Greene got in, and he would regularly spend time on the main campus, then take a bus and transfer to the metro and walk a few blocks to the law school.

In law school, Greene was able to rekindle his love of English literature by taking “every class offered in English legal history.” He explains, “You can trace a lot of English legal history in the literature,” and “there were a lot of English writers who were lawyers.”

Greene came back to California and passed the bar exam in 1985. He started his legal career with Lawler Felix & Hall, one of the oldest firms in Los Angeles at the time. Greene then moved to Buchalter (then known as Buchalter, Nemer, Fields & Younger).

“I worked in a fairly small department that did municipal bonds,” Greene recalls. “As the lowest person on the totem pole in that department, I spent hours on end doing due diligence research.”

He remarks, “It can be a deadly dull area, but I found it fascinating.”

Greene says he “became interested in the government agencies” for which the firm was “doing the bond work for,” noting:

“…I developed an interest in writing about those agencies and how they worked.”

Disenchanted With Practice

As Greene was learning about the practice of law, he was also learning that “law practice wasn’t for me.”

At the time, he was dating a woman who worked at the Los Angeles Times as a financial analyst. She was encouraging him to consider other career options and talked him into taking a copyediting class through the UCLA extension program.

She also told Greene that there was a building catty-corner from the Times office (which was then still on Spring Street in the Civic Center) where there was a “law-oriented newspaper” that was looking for “attorney journalists.”

As it happened, one of Greene’s classmates in his copyediting class had applied to the newspaper his girlfriend was describing: the MetNews. The job didn’t work out for his classmate, but the girlfriend convinced Greene to give it a shot himself.

He walked in, intending to just pick up a job application, but was given a copyediting test and a quiz on current and historical events, and was then ushered into the office of MetNews Editor/Co-Publisher Roger M. Grace.

Grace offered him a five-day trial position, and Greene accepted.

“I was intimidated” coming in without any journalism training, Greene says, but, he recounts. the staff eagerly welcomed him into the fold.

Kenneth Ofgang “took me under his wing immediately,” Greene recalls. Ofgang had been with the newspaper about three years by that point. (He would spend a total of 27 years with the MetNews before his death in 2017.)

“Ken taught me how to do what I needed to do,” Greene says.

At the MetNews, one of the topics Greene focused on was a dispute between then-Mayor Richard Riordan and the City Council on reforming the city charter.

“Roger basically gave me free reign to write about the charter reform,” Greene says, “and that turned out to be a two-year project.”

Greene not only wrote news stories on that topic but in expressing views on it, had his first taste of writing opinion pieces on a subject.

Encounters Former Classmate

His job also brought him into contact with Krinsky in a professional capacity, as she served on the city Ethics Commission and was president of the group for two years.

“A lot of issues Rob covered in city government was during my time on the commission,” Krinsky says, but advises that he never let their friendship skew his coverage.

“There were often issues on which we didn’t agree,” Krinsky recalls “He never pulled any punches, but he did it with a tone which left all sides feeling heard and feeling respected.”

When Greene wrote opinion pieces, Krinsky says, even when he was expressing a strong opinion, it was always “done in a respectful way” with “passion for the issue and a desire to convey information and understanding,” but “never tried to be hurtful or harmful even to those he disagreed with.”

Krinsky also says that when Greene is onto a news lead, “what might seem like a quick and easy story” is anything but.

“He’ll go that much deeper than anyone would have thought to go,” Krinsky remarks. “He’s always thinking about the larger context, the larger implications, and what wasn’t obvious at first blush.”

Greene will “never cut corners,” and she says she was sometimes taken aback by “how many nuances he’d find” including some that never would have occurred to her, even though she considered herself an expert on the topic of criminal justice.

“It’s a testament to Rob and the way he approaches things,” Krinsky declares. “He brings a deep curiosity and a desire to be tested, and to pressure test with those he respects, but at the end of the day he always brings his own independent thinking to it.”

Greene is “an unbelievably talented and brilliant writer,” but its “the intellectual curiosity and depth to everything he does” that truly sets him apart, Krinsky declares.

Enters Into Marriage

Shortly after Greene settled in at the MetNews, he made a major transition in his personal life by marrying the girlfriend who convinced him to take a stab at the job. Greene and Dana Chinn wed in 1993.

In 1996, Chinn made a career change, leaving the Times for a position with the Gannett media company.

For four years, the couple maintained a bi-coastal relationship, with Chinn in Washington D.C. and Greene in Los Angeles. It was hard to be apart, Greene says, but notes:

“We talked every night for hours, probably more than we would have if we had been together.”

After getting off work on Friday night, Greene would drive to the airport and take a red-eye flight to D.C., spend the weekend with his wife, and then fly home Monday morning in time to make it to work by 11 a.m.

“It all worked out very nicely,” Greene says.

Chinn eventually left Gannett and became a journalism professor at USC Annenberg. One of her colleagues was a writer for LA Weekly who told Chinn that the publication was hiring.

Greene “was interested in trying longer-form journalism,” which was something the MetNews didn’t offer as a daily publication, so he made the tough decision to leave after 11 years.

At the LA Weekly, Greene says, he learned about some issues and movements of which he had previously been unaware. Affordable housing, poverty and social justice were new topics for him to explore in a magazine format which allowed him to include his perspective as opposed to the objectivity required of a straight news writer.

His three years with the magazine “sort of allowed me to expand my understanding of the justice system, which has always been extremely important to me in part because my father lived and breathed respect for the justice system and the institutions of justice,” Greene says. “I began to understand that law is a constantly developing thing and that legislation constantly needed to be reviewed in order to protect and expand justice.”

Recruited by Times

In 2006, the editor of the editorial section for the Times called and asked him to consider coming on board.

“I think they liked the snarkiness they read in the LA Weekly,” Greene says. He had gotten feedback from readers that “they liked my stuff because it was snarky,” but he says “it’s hard to cover the government without getting a little snarky.”

Greene also says it was “unusual” for the Times to take “someone from an alternative weekly with an antiestablishment perspective” to be a part of the editorial board for “the ultimate establishment perspective,” but “when I joined, the editorial board had a very ‘establishment-liberal point-of-view’” supporting free markets and free enterprise. “I was comfortable with that,” Greene says.

Jim Newton was the editor of the editorial section from 2007 through 2010. He says Greene is “the only person I know who cared as much about charter reform in the City of L.A. as me,” which led to “a lot of wonky conversations, and lots of fun.” Out of the 25 years he spent with the Times, Newton says, the three years he had on the editorial board with Greene were the best.

On the board, Newton explains, the “goal is to produce collaborative work,” and “upwards of 80% of the editorials we wrote in our time reflected a consensus view.” He says “there definitely were some we split on,” and “sometimes those conversations could get rough,” but Greene was always “a voice of compassion.”

Greene “was a good listener, and a patient listener” who would respond to proposals “with just the right amount of deference and critique,” Newton brings to mind. “I don’t remember Rob ever being shy about arguing,” but he “is a respectful advocate and certainly a respectful colleague.”

Newton adds that they “didn’t have many occasions to disagree,” and if they did, that would make him question what he believed to be right.

“I’ve heard that from others as well, because they respect [Greene] so much,” Newton relates. “I don’t think there was any more influential voice during the years I was on the board.”

As a writer, Newton says, Greene was “such a rare combination of someone who is deeply interested in the fate of the city but also individually very kind to the people he deals with in his coverage.” Greene is “very organized and methodical,” with “a real sense of how there is coherence between issues,” he continues, noting that Greene “didn’t write editorials that sought to demonize or belittle the other side of an argument,” and was always sure to “make sure our principles were well-considered.”

To hear Greene tell it, he initially stuck to his bread and butter, the politics of the city and county, and, he says, “the positions I wrote weren’t particularly political or partisan.” Greene characterizes them as “the sort of issue-by-issue opinions that fit in with the Times perspective on things,” and not “a particular change” from the opinions Greene had expressed before. However, “the longer I was there, and the more I learned about issues, especially issues of justice, the more I came to believe that in order to fulfill its mission of justice for all, the justice system had work to do,” Greene says.

Social Justice Issues

The lawyer/journalist had a front row seat to a lot of social justice issues via his longtime friendship with Barbara Osborn. Osborn met Greene while he was still at the MetNews, and after she became the director of communications for the Liberty Hill Foundation, a social justice advocacy group, she began inviting Greene to events where he could hear from community residents fighting oil drilling in their neighborhoods, seeking better policing in MacArthur Park, or trying to implement the Mello Act ordinance to preserve affordable housing.

A lot of the persons at these events were not comfortable in the presence of a reporter from the mainstream media, but “Rob paid his dues,” Osborn says. She adds that Greene “was not stuck in his comfort zone,” and was willing to come to events where he stuck out like a sore thumb “in his khaki shorts and white button-down shirt,” just to hear what the community members had to say.

“That’s the thing that impressed me the most,” Osborn recalls. “He is genuinely inquisitive, genuinely thoughtful, genuinely trying to understand where people are coming from.”

He built a level of trust with the residents that Osborn says she has never seen from any other reporter. Greene “was literally the only reporter at the LA Times” to whom some of these people would speak, Osborn recalls. “It was not that he was always writing things they agreed with, it was about the respect that he accorded them, about his willingness to listen.”

Osborn went on to become the director of communications for then-Los Angeles County Supervisor Sheila Kuehl. She remembers there was a plan to create a new women’s jail in Lancaster which, as Osborn saw it, “was just a horrible idea.”

Greene wrote an editorial describing how it would take more than one day for a person dependent on public transportation to make the trip from Long Beach, near the southern end of the county, to visit a loved one at the jail site in Lancaster, due to the distance and the lack of public transit in the northern part of the county. Osborn says the editorial came out shortly before the jail project was coming up for a vote, and once Kuehl read it, the county lawmaker said she was voting against the project.

Criminal Justice System

Greene says he began focusing on the criminal justice system, in particular, after the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2011 decision in Brown v. Plata finding that the overcrowded conditions of California’s prison population violated the Eighth Amendment. The court ordered the state to reduce the prison population, and then-Gov. Edmund Brown Jr. proposed the Public Safety Realignment Act as a way to reduce new prison admissions.

“A lot of elected officials and police officials opposed it,” Greene says, but “in opposing it, they were describing realignment incorrectly.”

Greene says “the falsehoods really bothered me, and so I began writing editorials for the Times about the falsehoods.” That led him into writing about various efforts at criminal justice reform.

While Greene’s writings have been sharply critical of what he saw as stark inequalities and shortcomings of the criminal justice system, he says his harsh words stem from “a deep respect for the justice system that was instilled from an early age by my father and only increased when I studied law and worked as a lawyer.”

Greene says he calls for reform not to tear down the system, but because “it is important to me to sustain it and defend it.” For the system to survive, he comments, “it needs to be constantly improving the way it actually delivers justice to people.”

He expresses a fear that “if a perception builds that it’s a system that treats people differently based on how much money or influence they have rather than what the law is, and what the truth is, and what justice is, that it could fall under its own weight.”

Greene says that he tries to be mindful that when he is critiquing a policy, position, or person, he has to “be forthright, without being cruel.” Learning how to disagree without being disagreeable is “a hard lesson,” but there is “a difference between snark and meanness,” and “a little bit of snark is OK,” he declares.

Editorial-Writing Excellence

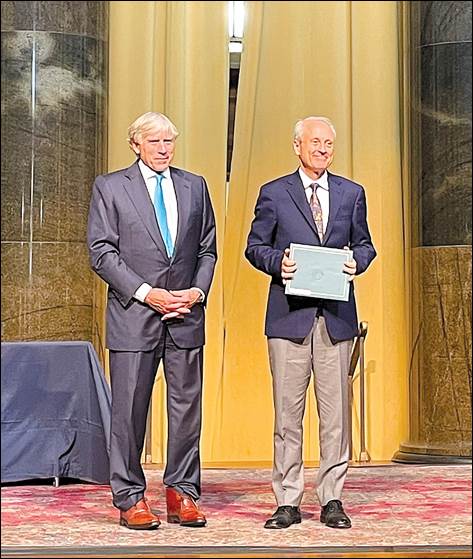

Or maybe it’s more than OK. Greene’s series of editorials on bail reform, juvenile justice sentencing and the plight of prisoners during the COVID-19 pandemic won him the Pulitzer Prize for editorial writing in 2021.

“It was a thrill,” Greene says. “It was an absolute thrill.”

|

|

|

Greene accepts the 2021 Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Writing from Columbia University President Lee Bollinger. |

During his days at the MetNews, Greene relates, every year when the Pulitzer recipients were announced, Ofgang would look and say, “Well, another year we didn’t win.” Greene says they would laugh “because the idea of one of us winning seemed so silly.”

Greene says that in receiving the award, he learned something he “did not expect to learn, which was something like that could happen.” He reports that he “immediately thought of Ken” when he got the news, as “the prize is as much [his] as it is mine.”

Despite having the highest honor an American reporter could ever receive, Greene has not been resting on his laurels. He continues to lend his pen to advocate against what he regards as untruths.

Opposition to Trump

Greene says he—and the Times—had been “staunch opponents” of President-Elect Donald Trump because of what he characterizes as Trump’s “contempt of the news” and “contempt for the truth,” adding:

“We saw him as a danger to democracy and a danger to the institutions of justice.”

The editorial board had prepared an endorsement of Vice-President Kamala Harris in the general election. But Soon-Shiong blocked the newspaper from running the editorial.

“My opinion is if he did not want to follow through on the stand we had taken and the principles we had expressed, it was incumbent on him to have said so months ago,” Greene maintains.

When the endorsement was yanked, Green resigned in protest.

Additional resignations and a slew of canceled subscriptions followed the Times’s decision as well.

Osborn says that Greene once made a comment to her about how “cowardly leaders leading cowardly institutions will cave in anticipation of power” and says that she thinks that’s how Greene feels about the Times’s decision.

“This was a moment to show some character, some courage,” Osborn maintains, providing her assessment that Greene did, the Times did not.

Newton remarks:

“A wise editor once told me the only way to be effective and principled in journalism is to be willing to walk away from it.”

He reflects:

“Rob reached that point, and I commend him for it.”

For his part, Greene says he remains optimistic about the future of the free press.

“Just like a person, an institution’s strength develops when it’s tested,” Greene says. “Right now, our institutions are being tested, but if we can help shore them up, we can hope they will emerge stronger.”

Copyright 2025, Metropolitan News Company