Special Section

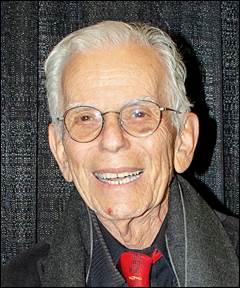

PERSONALITY PROFILE:

ARTHUR GILBERT

Many Regard His Judicial Opinions as Unexcelled in California

By Sherri Okamoto

Court of Appeal Presiding Justice Arthur Gilbert of this district’s Div. Six is accustomed to creating harmony—with litigants at odds, with a clumsily-worded draft opinion that needs revision, with fellow jazz musicians while jamming, and with his own packed schedule.

On a late afternoon in late fall, Gilbert wryly reflects that he’s “always doing 12 things at the same time” and predicts that his “Person of the Year” profile would end up being more of a portrait of “Gilbert in action.”

It’s not just that he is in constant motion—although his slender form rarely stays put behind his desk, and his lithe fingers almost never are still—but, Gilbert says:

“I’ve got all these things rolling around in my mind all the time, and I can’t shut it off.”

Perhaps this is the secret behind his legal acumen, his sharp wit, and his analytical writings, as well as his accomplished musicianship.

Gilbert says what he loves about jazz is that it is “exciting” and “never the same,” because the musicians are always improvising on the chords and putting their own unique spin on each tune. It is therefore a fitting genre for the multi-talented jurist who has always done things his way: a little unconventionally.

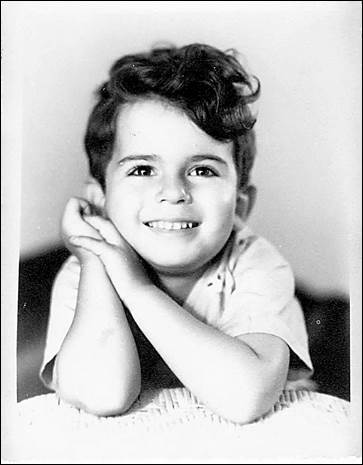

Even something as simple as being born wasn’t a straightforward entrance into life for Gilbert. As might be fitting for a future legal star, he was born in Hollywood—but he almost didn’t even have a shot at life.

“I was born dead,” he says. “A blue baby, with no heartbeat.” According to the medical records, doctors had not expected him to be revivable, but, Gilbert says, “I got smacked around.” He came to.

Gilbert was his parents’ only child. His father was a professional pianist, and his mother played as well. She was Gilbert’s first teacher. As was typical for women of the time, Gilbert’s mother didn’t work outside the home, but “she was a liberated woman and didn’t know it” because she was not domestically inclined either, Gilbert recalls. “She didn’t like to cook and things,” he says, so he and his father often helped with the housework.

The family home was unusual in that it wasn’t a house or an apartment. The Gilberts lived in the Cadillac Hotel, on the beachfront between the Venice pier and the Santa Monica pier.

“It’s still here,” Gilbert says, “but it’s sort of a run-down place now.”

The nation was also in the midst of World War II, and so at night, there were government-enforced blackouts to avoid creating potential targets. He wasn’t allowed to go out onto the sand to play at the beach. either.

One thing that Gilbert says he remembers vividly was that there was a married couple who ran a movie theater at the Venice pier, and he would see them walking along the boardwalk, and then sitting on a bench together, holding hands the whole time.

“I can see them now, 80 some years later,” Gilbert says, “They made such an impression on me.” Their devotion to each other was evident, he remembers, “and I was touched by it even as a child.”

Being moved by the open affection between a husband and wife is hardly commonplace for a young boy. Gilbert says he saw other things most children of his generation did not. His parents would have friends over and they were an “artistic bunch,” of the “bohemian sort,” welcoming gays and other socially stigmatized groups of the time.

Junior High School

Gilbert attended Le Conte Junior High School, which was “a really rough place” to be—especially as “a slight, skinny kind of kid,” he brings to mind.

As a student, he was no angel.

“I was the class clown,” he admits. “I got a lot of laughs and I got in trouble a lot.”

Still, he had a way with words, even as a young age, and he says he was usually able to talk his way out of any serious punishment for his misdeeds.

At Hollywood High, Gilbert says, he began to dabble in writing.

“I wrote all kinds of things,” he remembers. “I wrote essays that were funny for class, and I got published in a poetry magazine for kids.”

Back then, Gilbert says, he was “torn” between pursuing a career as an author, or as a jazz musician, which were “two very impractical professions” that did not thrill his parents.

He prevailed upon them to pay for piano lessons with Sam Saxe—one of the few jazz piano instructors at the time. Saxe “told me how talented I was, how good I was,” Gilbert says, but “my parents said, ‘Whatever you do, don’t become a jazz musician, please.’ ”

Gilbert didn’t pursue fame as a pianist, but he did help some of his classmates—a singing group calling themselves The Four Preps—by filling in as their rehearsal pianist when the regular pianist wasn’t available.

The Four Preps performed at the Hollywood Bowl, on Your Hit Parade, and on the Ozzie & Harriet Show, Gilbert notes. The group would go on to place 13 singles on the U.S. charts between 1956 and 1964, with their biggest hit being “26 Miles (Santa Catalina).”

Becomes a Bruin

For his part, Gilbert went off to college at the University of California, Los Angeles.

“In those days, if you had decent grades, you went to college” Gilbert says. UCLA was relatively inexpensive and close to home, so it was an easy choice for him.

“I never even thought about going ‘back east’ or anything,” Gilbert notes. “I was a California kid.”

Gilbert says he was part of a small jazz group that played a few gigs while he was at UCLA, and he continued to write, with his magazine pieces on jazz music and musicians being published.

He graduated in the winter of 1959 with a degree in English.

“I wasn’t sure what to do with my life,” he says.

|

|

|

Gilbert sits with Court of Appeal Div. Six Justices Steven Z. Perren (now retired), Kenneth R. Yegan, and Paul H. Coffee (now deceased). |

The Vietnam War was raging at the time, and he was “vehemently opposed to it,” so the one thing Gilbert said he was sure of was that he wanted to avoid the draft.

“Being a lawyer was not the priority,” which he says he is not proud to confess, but “I felt it wouldn’t hurt to get a law degree because it would be a way, as one of my friends said, or having tools to fight in the figurative jungle.”

Gilbert also wasn’t sure where he wanted to go to law school. He applied to what was then-Boalt Hall (now the University of California, Berkeley School of Law) and to Harvard University.

“Harvard didn’t respond right away,” Gilbert says, but Berkeley did.

“Berkeley was a happening place in the 1960s,” Gilbert recalls, “so I went to Boalt.”

After finishing law school, while waiting for the bar exam results, Gilbert took some graduate-level courses in English literature at Berkeley, but when he found out he had passed, Gilbert says, he “didn’t see any point in continuing” the studies.

“I figured I’m a lawyer now, maybe I should do something with the law,” he recounts.

City Attorney’s Office

Returning to the City of Angels, he was hired as a deputy Los Angeles city attorney, but after about 18 months, decided to move into the private sector. He initially interviewed with a large firm but seeing the office packed with cubicles was a turn-off. Gilbert chose a small firm instead, where he stayed for nearly 11 years.

Gilbert made a brief foray into politics in 1974, when he happened to be dating then-Los Angeles City Councilman Ed Edelman’s sister-in-law. Edelman made a successful run for the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors that year, and Gilbert took a leave of absence from his law firm to help manage Edelman’s campaign.

Gilbert says he was also “a candidate for City Council for about 10 minutes,” as a prospect for the seat Edelman vacated, but another Ed, a classmate from Berkeley, had another opportunity for him.

Edmund G. “Jerry” Brown in 1974 was then mounting the first of his four successful campaigns for the governorship and he asked Gilbert to be a part of the effort. Shortly after Brown took office, Gilbert recalls, a vacancy came up on the Los Angeles Municipal Court, and he sent a note to his friend asking to be considered for appointment.

“I didn’t have any illusions of grandeur,” Gilbert says, but “I was single, I had no debts and I wasn’t sure I wanted to continue [in private practice].”

He says there’s a quote he’s used often through his life, that he credits to French scientist Louis Pasteur: “Chance, or luck, favors the prepared mind.” Gilbert says he takes it to mean, “You see what comes up and take a shot, you never know.”

Sometimes, Gilbert says, “you get places by virtue of who you know,” and since he happened to know the governor, he was tapped for the bench in August 1975.

Comfortable on Bench

“I found it was a place I belonged because I got tremendous satisfaction about being able to bring a conflict to a close,” Gilbert says. “It suited me a lot better than taking sides and representing a client, especially if it’s a client you don’t like and you didn’t feel good about it.”

Gilbert reflects that he “got quite a bit done at the Municipal Court,” implementing drunk driving programs, providing community service alternatives to jail sentencing, opening up the traffic court to let motorists come in at any time to contest tickets, and having tickets translated into Spanish.

In 1980, Brown elevated Gilbert to the Los Angeles Superior Court. He began handling Juvenile Court cases in Inglewood, but eventually was able to transfer to a civil courtroom Santa Monica. The assignment was ideal, he says, because the courthouse was three miles from his home. Gilbert remembers swimming and jogging during his lunch breaks, or going home to eat with his wife, Barbara (to whom he was wed Sept. 12, 1981).

“I was having the best time in the world,” he says. “Then I get this call from Jerry, appointing me to the Court of Appeal.”

Gilbert initially turned down the position, but his friend prevailed on him to think it over. After a day, Gilbert called Brown back to take the job. “He said, ‘Well, I hope you handle your cases with greater dispatch,’ ” Gilbert recalls.

This district’s Div. Six—serving the counties of Ventura, Santa Barbara, and San Luis Obispo—had just been created, so “we didn’t have a courthouse, no building, nothing,” Gilbert says. For a time, he worked out of Justice Elwood Lui’s chambers in Los Angeles.

Lui recalls that “people would ask Justice Gilbert how it was being on the Court of Appeal, and he’d say, ‘When you get there, you get a roommate,’ which was me.”

Then, Gilbert “would complain I made too much noise,” Lui says, “and I’d tell him, ‘Hey, I invited you, you’re a guest here.’ ”

Now, Gilbert has his own space on the second floor of a building in Ventura known as “Court Place,” with his office overlooking downtown Ventura.

“He’s the only judge or justice who has his own balcony,” Lui says. “My room is a little bit bigger, but it’s not as scenic here, and there’s no ocean breeze.”

Original Members

Justice Richard Abbe (now deceased) and Steven Stone (a mediator/arbitrator) filled out the original bench of Div. Six.

“We were three very different people from different walks of life, but we became the closest friends you can imagine,” Gilbert says. He has a photograph of the three of them, and their respective wives/girlfriends, taken on the beach during those early days of the court, still on prominent display in his chambers.

“We have always been very close in this division,” Gilbert says. He notes that he maintains the collegiality with his new brethren.

“I have a theory about how courts should be,” he says. “My idea was that we should have an open court where everyone talks about anything to anyone they want—that way we get a plethora of ideas and are in a better position to come to an informed decision.”

Gilbert contends “our role, as a court, is to turn out the best product we can, and our collegiality is absolutely vital” because “if you keep your chambers sort of separate from everyone else, you’re being cut off from other ideas.”

During the course of the interview for this profile, Gilbert’s door is wide open, and a regular stream of attorneys and staffers freely come and go, asking questions, giving feedback and providing updates on pending matters.

“Everybody is on a first name basis,” Gilbert says. “I’ve kept it that way with all the people that have been in this division.” He says takes pride in the court being “open, and warm, and friendly.”

Crafting Opinions

Gilbert says he also takes pride in crafting opinions.

“When I got here, I had written stuff and people had liked my writing, but I was thinking to myself about what approach I should take” with appellate opinions, Gilbert says. Since he had studied the musicians he admired to improve as a musician, he decided to do the same thing with the law.

“I looked at the great jurists—Justice Traynor, Justice Cardozo, etc.,” Gilbert says, referring to California Chief Justice Roger Traynor and Benjamin Cardozo. The latter’s writing skill was displayed as a chief judge of the New York Court of Appeals and as a justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

“I read their opinions and looked at their style of writing and I used that as a model,” he recounts.

Lui, however, says he remembers the process being a little simpler. “I edited his first opinion, Lui says. “He claims I made a lot of edits and he accepted them.”

When asked about the state of that first opinion, Lui just laughs and says:

“He’s a very good writer, one of the best. He was just a little nervous about his first opinion.”

To many, Gilbert is seen as unsurpassed in writing skill among California’s appellate court justices.

It’s known that Gilbert does put a lot of thought and effort into crafting his opinions. When a staff attorney walks in and shows him a draft, Gilbert will question the phrasing of a sentence and say that it could be clearer. He also says it’s important to remember the decision is going to be read by more than one audience—there are the litigants, attorneys, and the general public.

He relates that opinions must often be rewritten “to be understood.”

Witkin’s Treatises

Gilbert expresses the view that treatises authored by the late legal scholar Bernard Witkin provide a good example of writing to be understood, elaborating:

“You can read his treatises and you know what he’s talking about.”

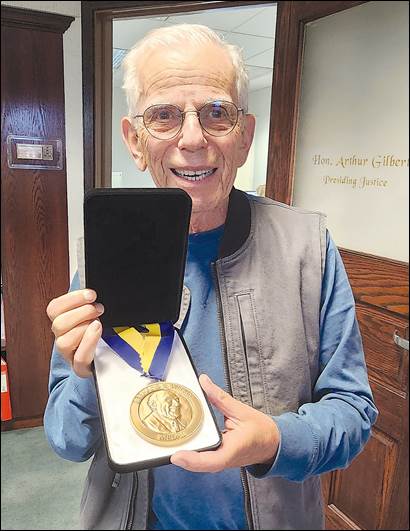

Gilbert says he admired Witkin’s style, so it means a lot to him that he was the 2024 recipient of the Bernard E. Witkin Medal from the California Lawyers Association.

The medal is awarded annually to a member of the legal community who has helped shape the legal landscape through an extraordinary body of work, and its namesake was the first recipient of it in 1993.

|

|

|

Gilbert poses for a photo with his Bernard E. Witkin Medal awarded to him by the California Lawyers Association in 2024. |

Gilbert says he is “not really an awards guy.” As it is, however, he has been the recipient of a long list of them, including the Los Angeles Bar Association’s Outstanding Jurist Award, the Beverly Hills Bar Association’s Award for Judicial Excellence, the Los Angeles County Law Library’s Beacon of Justice Award, the Appellate Justice of the Year for the Consumer Attorneys Association of Los Angeles. But he keeps the Witkin Medal displayed in his chambers because Witkin, now deceased, had been a friend and major influence on how he fashions his own writings.

Gilbert says that his own approach is to provide an opening in an opinion that tells “what the case is about” which “informs the reader” whether he or she “should bother to read the thing.” His introductions are characteristically pithy and enticing.

One such opening is this, in a 1994 opinion:

“If this case is an example, the term ‘civil procedure’ is an oxymoron.

“Plaintiff’s attorney appeals a discovery order that he pay $950 in sanctions. We echo the trial court’s comment when he reviewed the facts that gave rise to this order: ‘Unbelievable.’ What is believable, however, is that the order is not appealable. Nevertheless, we treat it as a writ petition. No court should have to review these facts again.”

Zukin Comments

Court of Appeal Justice Helen Zukin of this district’s Court of Appeal Div. Four passes on that Gilbert is considered by many in the legal community to be “the poet laureate of the California courts,” and expresses the view that “he really is.”

Gilbert is “a master wordsmith,” who “has set a really high bar for anyone in this profession to even come close to,” Zukin declares, saying that his opinions show “he cares so deeply about his cases and the law.” She adds that they’re also “practical” and sometimes “infused with just wonderful humor.”

The Div. Six presiding justice has been “an incredible mentor” to many on the bench, and has taught several courses on legal writing, she advises, relating:

“He says it’s all about the facts. The first and last question is: What is this case about? What is the real dispute?”

The jurist’s role, in his view, is to “distill it down until you understand the case and the way it needs to be resolved,” then “apply a common-sense test” to that resolution, Zukin says, noting:

“These are all things he’s told me in his own words.”

‘Brilliant Writer’

Encino-based attorney Robert A. Schwartz agrees that Gilbert is “a brilliant writer” whose opinions “are a work of art.” The opinions “don’t waste a single word,” but can still incorporate lyrics from songs, verses from poems, or other references to famous historical works.

“Over the course of his career writing thousands of judicial opinions on the Court of Appeal,” Schwartz says, Gilbert “has created several memorable phrases or lines which will be remembered forever,”.

He points to one 1985 decision granting a writ of habeas corpus, thus vacating a man’s convictions of driving under the influence and driving with a suspended license. Gilbert quipped:

“Our review calls to mind that one or more of a defendant’s constitutional rights may occasionally fall between the cracks; here, many of them fell into the Grand Canyon.”

(However, a rehearing was granted and, in a new opinion, Gilbert wrote that “certain constitutional rights” of the defendant were violated; the language that caught Schwartz’s attention was eliminated.)

Samples of Writings

Looking at a few of Gilbert’s decisions:

•The justice in 1986 wrote, memorably:

“This is a death penalty case. We reverse. Missy, a female black Labrador, shall live, and ‘go out in the midday sun.’

“Petitioners Susan, Russell and Mary Phillips appeal the judgment of the trial court denying their petition for a writ of mandamus….We reverse the judgment and hold that an ordinance permitting the county to destroy a dog without a noticed hearing to the dog owner who requests one is constitutionally infirm.

“We resist the temptation that grabbed hold of our colleagues who have written dog opinions, and will not try to dig up appropriate sobriquets. You will not read about ‘unmuzzled liberty.’ Nor will you consider an argument ‘dogmatically asserted,’ or cringe with ‘we con-cur.’ ”

Those quotes were taken from a 1970 Court of Appeal opinion. Gilbert continued, alluding to a phrase in a 1970 Court of Appeal decision:

“We will not subject you to phrases such as ‘barking up the wrong tree.’ ”

He declared:

“We disavow doggerel.”

•An attorney filed a lawsuit on behalf of a child who had lost a spelling bee. The trial judge sustained a demurrer without leave to amend and an appeal was taken from the ensuing judgment of dismissal. Gilbert said in a 1989 opinion:

“Question—When should an attorney say ‘no’ to a client? Answer—When asked to file a lawsuit like this one.

“Master Gavin L. McDonald did not win the Ventura County Spelling Bee. Therefore, through his guardian ad litem, he sued. Gavin alleges that contest officials improperly allowed the winner of the spelling bee to compete. Gavin claimed that had the officials not violated contest rules, the winner “would not have had the opportunity” to defeat him. The trial court wisely sustained a demurrer to the complaint without leave to amend.

“We affirm because two things are missing here—causation and common sense. Gavin lost the spelling bee because he spelled a word wrong.”

Gilbert went on to say:

“Our courts try to give redress for real harms; they cannot offer palliatives for imagined injuries.”

He proclaimed:

“As for the judgment of the trial court, we’ll spell it out.

“A-F-I-R-M-E-D.”

•In 1983, Gilbert wrote an opinion reversing a summary judgment in a case where a water district was the entity that should have been sued but the plaintiff, instead, named the sanitary district as the defendant. A lawyer represented both entities; the mistake was not pointed out by that lawyer who instead proceeded to file an answer on behalf of the sanitary district; the plaintiff’s lawyer eventually realized his error and made an effort to recover from it, proceeding against the correct party; summary judgment was obtained by the water district based on a statute of limitations. The trial judge was compelled to rule as he did based on the 1942 Court of Appeal decision in Kleinecke v. Montecito Water District, Gilbert said, but wrote:

“Our examination of Wright brings us to an inescapable conclusion. Wright is wrong. Its holding achieves an unjust result which should not be repeated here. Equitable estoppel as a bar to asserting the statute of limitations should have had its place in Wright, and it will have its place in the case at bench.

“As the clock ticked, the statute of limitations floated ominously near, camouflaged by the sham answer of Sanitary District. This allowed Water District to sleep through the proceedings. Such an opportunity to beguile one’s opponent usually occurs in dreams.”

He observed that “[d]reams, however, even when they come true, last only ‘Till human voices wake us, and we drown’.” The quoted phrase was from T.S. Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock.”

•Gilbert was saddled in 1991 with what he termed the “unenviable chore” of deciphering the meaning of Penal Code §1203.2a relating to sentencing. He wrote:

“The statute reflects a disregard for careful drafting and contempt for the English language. Meandering clauses in which the subject and predicate are ruthlessly separated from one another, jumps in thought and logic, and a lack of organization make the going difficult. Nevertheless, we have persevered in our trek through the statute’s thicket of tangled clauses. Our efforts have not gone unrewarded. The statute has a specific meaning that apparently was not discernible to other courts.

“The first paragraph could be used as a device to drive surplus students out of law school. It consists of one sentence, one hundred seventy-seven words long.”

•A lawyer said in his 1999 brief on appeal, “If there is a case that needs to be reversed, it is this one.”

Gilbert quoted the lawyer (now a Los Angeles Superior Court judge, Randolph Hammock) and wrote: “We agree and reverse.”

A lawyer had filed a complaint timely but the Clerk’s Office mailed it back owing to a trivial defect. It was received by the lawyer 20 days later, refiled promptly, but by then the statute of limitation had run, and the defendant was granted a summary judgment. Gilbert’s opinion reversed the judgment, saying:

“It is difficult enough to practice law without having the clerk’s office as an adversary. Here, paltry nit-picking took the place of common sense and fairness.

“Where, as here, the defect, if any, is insubstantial, the clerk should file the complaint and notify the attorney or party that the perceived defect should be corrected at the earliest opportunity….That should create no more difficulty than returning all the documents with a notice pointing out the defects. To deny [the plaintiff] her cause of action for lack of a signature makes a mockery of judicial administration.”

•In an opinion in 2020, Gilbert counseled:

“A Court of Appeal opinion is an explanation for a decision. In most cases the opinion should contain only the necessary facts and law to support the issue or issues to be decided. To aid the litigants, their attorneys, and the public, the opinion should be concise, readable, and filed with reasonable dispatch. Generally, the opinion should not mimic law review articles.”

Another highly regarded author of appellate court opinions, William Bedsworth, who recently retired as a justice of the Fourth District Court of Appeal’s Div. Three, commented in an opinion later in 2020 that Gilbert had provided “sound advice.”

Authors Columns

In addition to penning decisions for the court over the years, Gilbert has also written more than 300 columns for the Los Angeles Daily Journal, selections of which have been compiled into two books. Schwartz says his personal favorite was one where Gilbert imagined how various legal briefs would have looked if they had been written by different famous literary figures, such as Ernest Hemmingway or E.E. Cummings.

“It was absolutely brilliant,” Schwartz enthuses, saying:

“It was funny, and just spot on. He really captured the essence of each one of those writers.”

Notwithstanding his longstanding association with that newspaper, he has frequently provided the MetNews with touching tributes to jurists for use in obituaries or for news stories on retirements.

Return to Music

Somehow, all of this did not keep Gilbert too busy to take on an additional activity. He says he “decided to get serious about music again” and joined up with attorney Gary Greene’s Los Angeles Lawyers Philharmonic, for which his wife has performed as a featured vocalist. The Gilberts have also participated with Greene’s later-formed Big Band of Barristers.

|

|

|

Bass player Robert Hirschman, Gilbert, his wife Barbara, and saxophonist Joe Di Julio perform with Gary Greene and the Los Angeles Lawyers Philharmonic in 2014 at the Walt Disney Concert Hall. |

Gilbert also played some gigs on his own, making appearances at the Jazz Bakery and the Vine Street Bar and Grill. He has a group of musicians who regularly come to his home to jam as well.

“It’s been a very satisfying several decades for me to be able to do the two things I love most,” Gilbert says.

Plans to Retire

He adds that he plans to retire this year.

“I think 50 years is enough,” and “it’d be good to give other people a chance,” Gilbert says. “It’s beyond my ken to even believe that I would be on the court this long.”

Then again, “I can’t even believe how old I am,” Gilbert says with a laugh.

Born Dec. 29, 1937, in Los Angeles, he’s 87.

He says he hopes to spend his time playing more music, reading, and enjoying the company of his wife and their two cats.

As for the legacy he leaves, Gilbert initially proposes: “At least he tried”? After a moment of reflection, he suggests: “Whether he was right or wrong, you understood what he had to say.”

Gilbert’s colleagues suggest that his legacy should be described far more effusively.

Zukin says it’s hard to suggest one, because Gilbert is “so talented.” What she says has been most striking to her over the years is how much Gilbert “cares about people.” He “has a heart, and he leads with his heart,” Zukin says.

She first met Gilbert when he was being considered for appointment as presiding justice in 1999, and she was the chair of the State Bar Commission on Judicial Nominees Evaluation (“JNE”). Zukin had been chair for several years by then, and she says she had seen “thousands of confidential comment forms” on candidates during that time, but she had never seen responses such as those Gilbert received heaping praise on him.

“It was clear to me how beloved and respected he was in the legal community,” Zukin says. Since then, Gilbert has become a friend and. she says, she has had the pleasure of seeing first-hand all of the qualities that earned Gilbert his “extremely well-qualified” JNE rating.

Schwartz says Gilbert is “a giant in the law, who has left a powerful imprint upon the law and the legal community.”

Gilbert is “remarkable,” “brilliant,” and “a person of unassailable integrity,” Schwartz remarks. “Truly one of the most extraordinary figures in the field of law.” But Gilbert is also “a person of great modesty and humility,” and “very reserved about telling the world about what he’s accomplished.”

He’s seen how Gilbert will “agonize over a lot of decisions” to “come to the right conclusion.” Schwartz says Gilbert is “revered,” and “not just because he’s clever, and not just because he can turn a phrase, but because he has a real deeply embedded sense of justice.”

Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Michael Harwin says he’s “known, and respected” Gilbert for more than 40 years. “I think he was the brightest guy on the Municipal Court, the brightest guy on the Superior Court, and I think he’s the brightest guy on the Court of Appeal,” Harwin enthuses. “He’s a true Renaissance man” as skilled with the piano as with a pen, he adds, who “knows a lot of things about a lot of things.”

Arthur Gilbert Courtroom

A concrete part of Gilbert’s legacy is that the Div. Six courtroom bears his name. Lui says the idea to name the courtroom after Gilbert came from Justice Steven Perren, now retired.

Perren advises that the idea was likely not unique to him, but he happened to be the first person to suggest it out loud. He had meant it as a way to honor his friend and colleague, but he jokes, it was also a bit of revenge. He relates that Gilbert had teased him for years about the fact that the Ventura County Juvenile Justice Complex bears his name, in recognition of the many years he had served as a Juvenile Court judge, so having the courtroom named after Gilbert evened the score.

“He should really have the whole building,” Perren says, “but we couldn’t do that because it isn’t our property, so I thought he should at least have a room named after him.”

But really, “honoring him honors the system,” Perren opines. “He is what judging is all about.”

Gilbert “represents the best of what the court can offer,” and “is what we should all be about,” Perren states. “He’s one of the great jurists in the history of the state of California.”

Perren says he considers Gilbert to be like a brother, as colleagues, friends, and as musicians. Perren is a trained singer, and he has performed with Gilbert accompanying him on the piano.

Manella’s Recollections

Nora Manella, a retired presiding justice of this district’s Div. Four, is a talented vocalist—at one time, an opera singer—who has had several opportunities to sing while accompanied by Gilbert on piano.

Although most of these occasions were organized events, Manella remembers giving one impromptu performance with Gilbert at a judicial conference a few years ago.

The event was at a hotel which had a grand piano in its lobby, and there was a sign on the piano that said in large bold-faced type “DO NOT PLAY THE PIANO.” When Manella and Gilbert saw the instrument, she says, they “took one look at each other and nodded.” Gilbert then slid onto the piano bench and began to play, and Manella began to sing.

“I can’t say I remember what songs Arthur played,” Manella says, but “he can play anything.” Odds were they were show tunes by George Gershwin, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, Rodgers & Hart, Rodgers & Hammerstein, Stephen Sondheim, and the like.

Before long, a half a dozen other justices and a contingent of Highway Patrol officers, there for judicial protection, had come to join them, Manella says. Some hotel guests were probably there, too.

“Needless to say, no one from the hotel intervened to enforce the no-piano-playing rule,” Manella adds. “Our own ‘lawless’ behavior, though probably violative of the judicial code of ethics requiring judges to act within the rules and with appropriate decorum, was a source of much mirth—at least to us.”

Manella posits, “We probably enjoyed it all the more for having broken the rules to engage in it.”

Schwartz comments that Gilbert does a rendition of the jazz classic “Body and Soul” that is “one of the most inspiring, almost divine pieces of piano playing I’ve ever heard.”

Bendix Comments

Court of Appeal Justice Helen Bendix of this district’s Div. One says Gilbert is “very accomplished” as a pianist, who practically “inhales music.”

Bendix herself plays the violin and the viola, but she says she would not put herself in the same category of musician as Gilbert.

She plays with the Lawyers Philharmonic, and she says one of her favorite performances was one where Gilbert and attorney Helen Kim of Norton Rose Fulbright performed George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” at the Disney Concert Hall.

The piece features a piano solo, which Kim, a Julliard-trained pianist, played. Gilbert then performed a jazz improvisation of the same tune. Bendix says it was “just thrilling” to experience from just a few feet away in the strings section, and that she thought it “took a lot of guts” to take such a famous composition into a different context.

Gilbert also memorably played the typewriter for a rendition of “The Typewriter” by Leroy Anderson, Bendix says. The composition features a typewriter as a percussion instrument, and is difficult because of the typing speed required to keep up with the tempo. Gilbert handled it deftly, and had fun doing so, because he “has a great sense of humor,” Bendix says.

Bendix also says that Gilbert has been “an inspiration” and “a mentor” to her, both on and off the bench. “To say he’s supportive would be an understatement,” Bendix declares.

Retired Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Burt Pines says that “of all the lawyers and judges I’ve known during the last 60 years, I’ve never met anyone like Arthur Gilbert.”

When he was the Los Angeles city attorney and Gilbert was on the Los Angeles Municipal Court bench, Pines recalls, there was a “debate” between them as to whether jail time was appropriate for first-time drunk drivers. Pines had his prosecutors arguing for it, and Gilbert was regularly ruling against it.

“Since then, he has always claimed to me that he won the debate,” Pines says.

But even though they did not see eye-to-eye on everything, the two are friends and when Pines was serving as the judicial appointments secretary to then- Gov. Gray Davis, he says he “had the honor of recommending” Gilbert for elevation from associate justice to presiding justice of Div. Six. Gilbert “received superlative recommendations” for the post, Pines says, and he was glad to be the one to relay them to the governor.

Pines adds that of all the decisions Gilbert has made, “marrying Barbara was his best,” as Barbara Gilbert is “his best advisor and confidant,” while being a “beautiful and talented singer” who is “invariably the star of the show” when the couple perform together.

As a justice, Pines says, Gilbert is “without dispute…one of the best writers on the California court.” For lawyers and judges, Pines opines, “words are the tools of our trade and no one uses them better than Arthur Gilbert.”

Gilbert’s opinions “come to the point in simple and understood language,” and are “exemplars of what a proper appellate decision should be,” Pines says, while Gilbert’s columns are “truly ‘Art-ful,’” with a mix of “humor and an insightful message.”

Pines declares Gilbert is “a real mensch,” and that the legal community, and the citizens of California are “indebted to him for his devotion and contributions to the judiciary and public service.”

Copyright 2025, Metropolitan News Company