Special Section

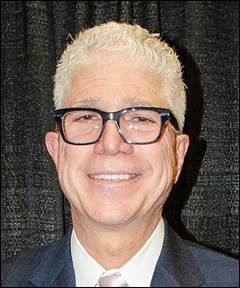

PERSONALITY PROFILE:

CHRISTOPHER FRISCO

A Second-Generation Judge, He Serves With Distinction as His Father Did

By Sherri Okamoto

“I had wanted to become a judge because I wanted to keep following my father’s footsteps,” Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Christopher J. Frisco says.

His late father was Charles E. Frisco Sr., a beloved member of that court who presided over proceedings in Downey for more than 28 years, retiring at the end of 1994. He officiated at 31 ceremonial enrobements of 264 judges, occasions marked by his humorous remarks.

In 2015, at age 92, he saw his own son sworn-in.

“I’ve lived in my dad’s shadow with no regrets, because my dad cast a very large shadow, and there was plenty of room for both of us,” the younger Frisco says, with pride. In fact, the first half of his own enrobing ceremony in 2015 was a moving tribute to his father—who would pass away a few months later.

Frisco discloses that his father was suffering from Alzheimer’s Disease and often became disoriented, so he arranged to have his him seated separately from the other members of the audience. After his father entered the courtroom, however, he seemed to recognize where he was—and he walked across the well to join the judges who were sitting in the jury box.

“He remembered he was a judge, and he wanted to join his colleagues,” Frisco says, choking up a bit at the memory.

Having seen multiple enrobing ceremonies by the time his rolled around, Frisco says he didn’t want his to be “a coronation,” as so many tend to be, with speaker after speaker heaping accolades on the newly-sworn judge. Frisco instead insisted on having speakers honor his father…and then razz him like there was no tomorrow.

“No one laughs harder at me, than me,” Frisco declares.

Frisco says he told his former boss, then-District Attorney Steve Cooley, to “go nuclear,” as Cooley “had a lot of material on me.” Cooley understood the assignment.

Cooley says Frisco’s enrobing was “one of the most interesting and memorable” that he has “ever attended,” noting:

“And I have attended many.”

Although Cooley recalls cracking a joke about the “collective IQ of the deputy district attorneys in the office going up” with Frisco’s departure, he says Frisco’s “sense of humor, collegiality and upbeat personality” were greatly valued.

“Among all the people I know, Chris Frisco is one of the most enjoyable persons just to be around,” Cooley declares. “We’re always laughing.”

When Frisco was a deputy, he and Cooley went on a tour of Avalon on Catalina Island so that Cooley could get better acquainted with that unique part of the county under his jurisdiction as district attorney. Cooley says “it seemed everyone, shopkeepers, sheriffs, court personnel” knew Frisco and were happy to see him. “I think that anecdotal experience I had with Chris was likely repeated in lots of other places” given Frisco’s friendliness, and penchant for engaging in conversation.

Six Siblings

Frisco posits that his ebullient nature is perhaps “a middle child thing.” Growing up as the fourth of seven children, Frisco says, he “sometimes got lost in the shuffle” because “you had to be very outgoing to be heard above the din.”

Frisco notes he was quite the chatterbox even as a child. “The nuns at the Catholic school all told my parents, ‘He sure talks a lot, he’s going to be a lawyer just like his dad,’” Frisco recalls.

|

|

|

Frisco is pictured here at the age of four. |

As a young child, Frisco says, he wasn’t sure what his father did for a living. “I knew every day my father would dress up in a suit and walk out with a briefcase, in a hurried rush,” he says. “He was always in a hurried rush, and funny enough, I’m the same way now in the mornings.”

He remembers that his mother would carry him out to his father’s car every morning so he could wave goodbye. “I knew he did something important, and I thought, ‘That’s what I want to do, I want to be just like my dad,’ ” Frisco says.

Initially, the judge recounts, he wasn’t conscientious about his schoolwork—but that changed in his senior year of high school when he found an old Triumph sports car he wanted. When he told his father he wanted to buy the car, Frisco relates, his father said, “I’ll allow you to buy it,” earning the money by getting “straight ‘A’s.”

Frisco’s response was:, “Really? That’s it?”

He got the grades, and he received the money to buy the car.

It didn’t all come from his father, however. Frisco earned some of the funds working as a janitor for the Downey Community Theater.” It was one of my best jobs because I could do my work and nobody would bother me,” he says.

He also worked as a ride operator at Disneyland, for the “It’s A Small World” attraction.

“That was the worst job I’ve ever had,” Frisco declares. “If I ever hear that song again, I’m going to puncture my own ear drums with ice picks.”

And, as luck would have it, the car that jump-started Frisco’s scholarly pursuits needed regular jump-starts itself, and other mechanical intervention.

“That Triumph never ran very well,” Frisco says. “There was always something wrong with it, and every time I drove it, it would break down, but it sure looked good in my driveway.”

Once he got his grades up, Frisco says, he continued to be a good student, but because he “had such a late start academically” he chose to go to Cerritos College to get some more courses under his belt before transferring to Pitzer College in Claremont.

Off to Italy

After graduating with a degree in philosophy, Frisco worked as a lease representative for a billboard company, striking deals with property owners to install billboards on their buildings, to earn enough money to travel to Italy.

While Frisco’s father and mother both lived into their 90s, his parental grandfather had died young. Since Frisco had never known his grandfather, he wanted to meet his grandfather’s brother, and he took Italian in school to be able to converse with the man.

“Well, that didn’t quite work out as planned,” Frisco says, because his elderly relative spoke only an antiquated Sicilian dialect. It took his uncle, translating to his cousin for Frisco, to have the long-awaited conversation with his grandfather’s brother. But Frisco still enjoyed the trip, and he has become quite the globe-trotter since.

Frisco has been to Japan, Korea, China, Thailand, Hong Kong, Spain, France, Germany, the Czech Republic, Costa Rica, Mexico, Egypt, South Africa, Lebanon, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, and England.

He has also returned to Italy several times—including a trip where he proposed to the woman who is now his wife, real estate investor Gianni Di Wang.

Frisco took Wang to the island of Capri, and during the trip, he pointed out the position of the planets overhead while they ate dinner. Jupiter was visible, as was Venus, in close proximity.

Given that Jupiter is the all-powerful king of the Roman gods and Venus is the irresistible goddess of love, Frisco says he thought there could be no better time to pop the question.

He seized the moment during a boat ride to an ocean cave known as the Blue Grotto, but when Frisco got on one knee, he nearly capsized the small vessel and terrified Wang, who was unable to swim. He almost lost the ring when she grabbed for his arm to steady herself—but he was able to hang on to both the bauble and his betrothed.

The couple wed in 2016, and now have a five-year old son. Little Giancarlo, not surprisingly, says he wants to be a judge like his dad.

Pursuits in Law

Of Frisco’s siblings, he’s the only judge, but two others became lawyers, and one married a lawyer. A granddaughter is also a practicing attorney, as are two cousins, and he has a nephew currently in law school.

Frisco himself went to Southwestern Law School, then spent a year in private practice working for the Law Office of Hiram Kwan.

Kwan, now deceased, mainly handled immigration cases but “did pretty much anything,” from bankruptcies to probate to contract to personal injury to criminal matters, Frisco says. That diverse practice is what initially attracted Frisco to the job, because he wanted to try at least one case in as many different areas of law as he could.

Frisco says he was looking for a learning experience, and what he learned was that he “hated all of it with the exception of criminal law.”

Criminal law “wasn’t paperwork, it was basically people skills, and I found that came naturally to me,” Frisco recites. “All the other technicalities of the legal profession, filling out forms, I didn’t really care for.”

Frisco’s first foray into criminal law was handling a driving-under-the-influence case for a friend’s employee. The friend had asked him to represent the employee, and when Frisco said “I don’t know how,” the friend said, “Well, learn.”

So Frisco took on the employee as a client, for free.

He turned for guidance to criminal-law attorney Thomas M. Byrne whom he knew through the Italian American Lawyers Association (“IALA”).

Byrne, who died in 2011, was not of Italian heritage—in fact, he was a president of the Irish America Bar Association. But he had space in the law office of Paul Caruso, one of the IALA’s five founders and its first president, and Byrne frequently attended IALA meetings. (Frisco’s father had been a founding member of that organization, and Frisco would go on to head the group in 2001.)

Frisco recounts:

“When I told Tom of my plight, he invited me to meet him in his office later that week. I showed him the police report and he spent hours teaching me about all the technical and procedural difficulties of a DUI. He went through that report with me using a fine-toothed comb.”

He notes: “I got the guy a good deal.”

The client was apparently happy enough with Frisco’s services that he called Frisco for help when he picked up another DUI charge.

Case Before Fox

That case went before then-Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Elden Fox, since retired. Fox recognized Frisco’s last name and told Frisco that when he had been a young deputy district attorney, Frisco’s father had been the first judge he appeared before. Fox related that Charles Frisco had been patient and kind to him.

Frisco remembers that Fox was gracious in overseeing his negotiations to resolve the client’s case. After the case settled, Frisco told Fox that he was interested in becoming a prosecutor, and Fox told him that he could use him as a reference in the hiring process.

Frisco explains that he wanted to join the District Attorney’s Office because as a defense lawyer, he “felt helpless” if he had a case where he believed the client hadn’t been properly charged, or the settlement offer seemed too high. “All I could do was force the case to trial and hope for the result, or convince the client to take a disposition that wasn’t fair,” and that just didn’t sit right with him, Frisco says.

“I figured as a prosecutor, I’d have the discretion to charge what was appropriate and to offer a fair disposition,” Frisco recalls. After 26 years as a DDA, and some 200 jury trials, Frisco says, he takes great pride, not in his conviction rate, but in having done justice.

In fact, there was one case where he secured a conviction but he had some concerns about some of the aspects of the trial. Frisco actually relayed these concerns to the defendant’s appellate attorney, and the appellate attorney was able to overturn the conviction. “I feel really proud of that case, because I was doing the right thing,” Frisco says.

There was another case involving a joyriding charge which Frisco dismissed after learning that the lead detective had not only failed to advise the defendant of his Miranda rights, but also lied under oath about this fact.

Frisco says Cooley had “drilled” into deputies:

“You’re in the truth business. We’re not here to get convictions, we are here to do the right thing.”

Frisco says, “I took that lesson very seriously,” adding that it served as his guidepost through many difficult cases.

Opportunity for Advancement

During his time as a DDA, Frisco handled special circumstance murders, death penalty cases, a high-profile rape matter, and several animal cruelty prosecutions. Then in 2013, then-Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Joseph E. DiLoreto presented Frisco with a new opportunity.

DiLoreto, now deceased (son of a founder of the law school now at Pepperdine), had been a neighbor while Frisco was growing up. The judge was planning to retire, and he endorsed Frisco to fill the seat he would vacate.

Perhaps in large part based on his surname—that of a judge with huge popularity in the legal community—Frisco ended up running unopposed in 2014. And it was DiLoreto who swore him in as a judge.

Frisco remarks that he was in training for a judgeship, as his father had been “a great teacher.” From his father, he says, he learned that “when you’re a judge, you’re a judge 24-hour a day,” and it is not just a job.

Taking the bench in January 2015, Frisco later became a member of the court’s Executive Committee.

Frisco has remained active with the IALA, of which all past presidents are board members, and he is a board member of the Los Angeles judges’ political action committee (“PAC”) as well as California Asian Pacific American Judges Association PAC.

While Frisco himself is not of Asian descent, he jokes that he is “Asian by marriage,” as his wife is a Chinese-American, and he says he was invited to the Asian Pacific board because of his work in supporting judges during elections.

Lebanese Ancestry

Frisco’s heritage is Italian on his father’s side, but his mother was Lebanese. The Lebanese have “a very strong cultural tradition and heritage of cooking,” Frisco says. As a child, he says, he spent hours watching his mother and her sisters preparing meals in the kitchen, because he was a “terrible athlete” who was left out when the other boys would go play baseball or basketball after school.

Looking back, “I felt somewhat traumatized I didn’t have the ability to play sports and there’s of course a certain social stigma to that,” Frisco says, “but the good side to that is that I do not suffer any life-long injuries…I’ve never had a concussion, I don’t have bad knees, I don’t have bad hips.”

The other benefit was that he learned to cook, and now he can churn out some scrumptious dishes, including a decadent seafood gumbo.

‘Wonderful Cook’

Deputy District Attorney Peter Cagney, a former colleague and long-time friend, says Frisco is “a wonderful cook,” who saved the day one year when the Compton office got off to a late start planning its holiday luncheon and they were having a hard time finding a place to go. Cagney says Frisco offered up a restaurant run by his sister and her husband. (At the time, the eatery was located in the City of Industry. Frisco’s Carhop and Drive-Thru is now in Whittier.)

Cagney says Frisco headed to the restaurant early, went in the kitchen, tied on an apron and whipped up 50 gourmet pizzas for his colleagues to enjoy.

Retired Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Allen Webster Jr. also speaks highly of Frisco’s culinary skill. Frisco knows good food, too. “He’s a gourmand, almost kind of a food snob,” Webster says. “He knows where to find the best of any type of cuisine.”

Often, the best food is to be found at Frisco’s home. “I’ve been to his house many, many, many, many times to eat,” Webster says, “and I have never had a bad meal at his house, even though most of things you eat there are things you’d never eat any other place.” It’s best to show up hungry, because there’s always multiple courses, perhaps starting with a cheese that’s been sculped into the shape of a flower and a special kind of bread that’s only available at one place in Orange County, and there’s wine paired with each round too.

“You have to eat all the food, and you have to drink all the wines, and it’s every kind of wine known to mankind,” Webster says.

Webster was born in New Orleans, and he says he has eaten “a lot” of gumbo in his life. He’s even learned to make it himself. But, he swears his is nothing compared to Frisco’s, which he describes as “off the charts.”

Frisco and retired Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Paul A. Bacigalupo share a fondness of Italian food, and Frisco knows how to prepare dishes from the various regions of Italy, the former jurist notes. “You could ask Frisco for a recipe, and sure enough he can tell you how to make a salt-baked branzino or tiramisu.”

Frisco has “even dabbled in wine-making and produced a pretty good bottle of wine,” Bacigalupo says.

Other Attributes

Cagney, Webster and Bacigalupo have praise for Frisco going beyond his culinary skills.

Frisco is “definitely one of my favorite people in the world,” and “one of the smartest,” Cagney says.

In addition to knowing the law, Frisco has vast knowledge of World War II and the assassination of John F. Kennedy, he imparts. Frisco has even gone to Dallas to see where Kennedy was fatally shot and, Cagney posits, it’s quite possible Frisco has figured out what really happened that fateful day.

Frisco is a problem-solver—logical, fair-minded, and even-keeled, Cagney says. In the courtroom, “he treats everybody with dignity,” and he’s always “cordial and polite.”

He was like that as a deputy D.A. too, the prosecutor recalls. Carney had been Frisco’s supervisor when they both worked in the Compton Courthouse, and they became good friends during that time.

Cagney then realized Frisco is “a really great guy, and a really terrible golfer.”

On the green “nobody swings the club as hard as he does, and the ball always goes hook or a slice,” Cagney reveals. But Frisco is “always going to be the best-looking golfer on the course,” as he is a sharp dresser with a fondness for Italian design, he says.

‘Always Late’

Webster met Frisco when Frisco was assigned to his courtroom as the calendar deputy. He recalls that the calendar “was always handled properly and smoothly,” but Frisco “was always late.” Every morning, Webster says, his clerk would be asking about Frisco’s whereabouts and the deputy would come hustling through the door.

History repeated at the swearing-in ceremony for Frisco, he recalls. Webster spoke about Frisco on that occasion. He says things were all set to get started, then the clerk looked around and asked where Frisco was, and Frisco came hurrying in, as had happened so many times before.

Part of the reason Frisco always ran late was that he “always had to visit with everyone in the courthouse,” Webster says. “Chris knew everybody.” And Frisco was always making introductions too. One time, he says, Frisco met a 90-something-year old juror who had known Webster as a baby, and Frisco brought the man over to visit with him.

“Everybody just loves Chris,” he declares.

‘Renaissance Man’

Bacigalupo says Frisco “is nothing short of a Renaissance man,” with “an understanding of so many topics and a display of expertise in history, especially Roman and Greek,” and a “razor sharp memory.”

Back when Frisco was a deputy district attorney, Frisco had handled the calendar in his courtroom in Compton. Like Webster, Bacigalupo recalls Frisco always rushing through the door in the mornings.

He was “always well-dressed,” but “the tie would be round his neck and untied” when Frisco would come through the doorway, Bacigalupo says. “The ritual” would be for Frisco to greet the staff, ask who needed coffee, then go over to the defense attorneys, ask how they were doing, then usher the attorneys into the jury room where there would be coffee and breakfast pastries.

“You had to first have the coffee and the pastry, had to socialize, catch-up, and then you could start talking business,” Bacigalupo says. Then, almost without fail, Frisco’s phone would ring and he’d scurry out of the courtroom with his phone to his ear, leaving his files spread out across the table. By the time Frisco would make it back into the courtroom, there might be a jury panel seated and attorneys at the counsel tables and Frisco would hastily gather up his papers with everyone watching, Bacigalupo says.

Even when he wasn’t harried, he reports, Frisco was a constant “man in motion,” observing that there was “always this energy flowing around him.” Bacigalupo, an IALA board member, expresses the view that “it was like this kind of Italian spirit that moves him.”

Frisco is “so witty and good-natured,” that working together was “so much fun,” and now Frisco is “one of the most generous friends I have,” Bacigalupo declares.

Frisco’s Humility

As a judge, Bacigalupo says, Frisco is “genuine and compassionate” and “really well-suited for being involved in the administration of justice.” For all his skill and talent though, he “has a lot of humility,” the retired jurist points out.

Reflecting that, Frisco was known to members of the IALA, prior to his election to the bench, as “Chris”; now that he’s a judge, he’s still “Chris”—just as his father was addressed as “Charley.”

“Like my father,” Frisco says, “ I ask people to call me by my first name unless I am in court, presiding over their case.”

Frisco’s swearing-in by DiLoreto took place in Bacigalupo’s courtroom in Compton. Bacigalupo says he remembers it “was just such a lively and festive occasion” with people lining the walls and hallways to be a part of the event.

“It was one of the most joyous occasions, I think, in his career, for him to have his father be present see him getting enrobed,” Bacigalupo says. “He’s a very family-oriented person, and it was so important for him to have [his father] present.”

‘Wonderful’ Performance

Retired Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Joan Comparet-Cassani says she remembers a particularly unusual murder trial Frisco handled before her, which “had everything” from prostitutes to a daycare teacher to a witness who got on the stand and said she had just taken some heroin. The cast of characters and their testimony was so bizarre, “it was almost unbelievable,” Comparet-Cassani recalls. “The jurors were just in shock, they had their mouths hanging open,” but Frisco, “was a very, very good attorney” and “knew what was coming” so he could present a strong case. Comparet-Cassani says she doesn’t remember how it ended, but Frisco’s courtroom performance “was wonderful” given what he had to work with.

Los Angeles Superior Court Judge J.D. Lord says he also was impressed with Frisco as a prosecutor. “If it was Chris Frisco for the People, the People were ready, as regular as rain,” Lord says. Frisco was “always prepared,” “respectful,” and “polite, maybe even to a fault.”

When rulings went against Frisco, “he didn’t behave like a petulant child, the way many lawyers do,” Lord says. “He would just press on and try to work around it.”

When he heard Frisco was running for a spot on the bench, Lord says, “I knew he was the ideal candidate.”

Frisco “is so patient” and “has a superior knowledge of the law,” Lord declares. “If you were going to mint a judge and wanted to take all the right ingredients, he would be the recipe.”

Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Laura Walton says she was a deputy district attorney at the same time as Frisco. But she only really got to know him, she notes, after she became a judge and he was the calendar deputy in her courtroom.

“He is a fantastic, standup guy,” Walton says, and did, literally, stand up a lot. She recalls that he was “always so animated,” often getting up and arguing while pacing about.

When Frisco said he was going to run for a judgeship, Walton recounts, she “absolutely” supported him, lending advice that he needed to “work on that poker face” and “learn how to be still.” Walton says she worked on those skills with Frisco up until he was sworn in.

The judge adds that Frisco’s swearing-in really showcased his “outgoing, fun personality.”

Frisco has a knack, she remarks, for “making everyone feel like family” and is “the most personable, loving, caring, will-give-you-the-shirt-off-his-back sort of person.”

Attorney/Sister’s Recollections

Frisco’s sister Janine M. Frisco-Poletti—a family law attorney and partner in Gilligan, Frisco & Trutanich who professionally goes by the surname of “Frisco”— says that all of her siblings looked up to, and admired, their father.

“Chris wanted to be everything he was,” Janine Frisco remembers. When her brother was sworn-in as a judge, he “had some awfully big shoes to fill,” but he has done it, she proclaims.

Even at home, “our dad was the perfect judge,” she says. When the children would argue, he would sit quietly, listen to both sides, then ask “key questions, right on point” to help them “use reason and logic, to understand,” or “make you think.” She says her brother “does that now,” and watching him on the bench, “you can just tell, it’s everything he ever wanted to be.”

As a child, though, Chris Frisco was “a challenge” to their parents, Janine Frisco says, remarking:

“His mouth always got him in trouble.”

It wasn’t that he was sassy. Rather, she says:

“He always had to know why—you always had to explain.”

And then he would pick apart the explanation given him or, at least, analyze the reasoning, she recalls.

Frisco used to pick on her and her three sisters, and making the others cry—but not her, the sister says, remarking that she’s as stubborn as he is.

Years later, when she had her first trial and opposing counsel was “such a jerk” to her, trying to make her break down and cry, she didn’t, Janine Frisco recounts, because she had all the years of practice enduring her brother’s taunts.

“As soon as I got out of there, I wanted to call Chris and tell him, ‘Thank you, you made me this way’,” she says.

But for all the teasing and pranks, she adds, “Chris just has a heart of gold.”

He’s the sort of person who would give away the coat off his own back, and it would be “some name-brand jacket—because he’s a fastidious dresser,” she says.

Older Brother Comments

Frisco’s older brother, Charles Frisco Jr., is a Long Beach criminal defense attorney. He says his brother is “very opinionated,” and sometimes “generous to a fault.”

On the bench, Charles Frisco says, his brother “never shows his philosophical or political beliefs” and is “the most passionate stoic I’ve observed in that position.”

Charles Frisco says his brother has the “utmost admiration” for the judicial system, and its “traditional formality and respect.” His brother also, in his view, “remembers what it’s like to be on the other side of the counsel table,” and comments that he would think that any prosecutor, defense attorney, or defendant would feel comfortable in Chris Frisco’s courtroom.

Copyright 2025, Metropolitan News Company