Special Section

PERSONALITY PROFILE:

KATHLEEN CADY

For Four Years, She Was State’s Foremost Proponent of Victims’ Rights

By Sherri Okamoto

The Greek philosopher Aristotle is said to have written, around 350 B.C., that the essence of life is “to serve others and to do good.” Attorney Kathleen Cady is the embodiment of that principle.

Cady came out of a well-earned retirement as a deputy district attorney to help families of murder victims and direct victims of sex crimes have a voice in the criminal justice system. Over the past four years, she’s been an advocate for more than 200 clients—without charging a cent for her services. And there’s no question that she did good, making sure the victims of crimes were not forgotten, and spurring changes in the law.

To date, Cady says, she has attended approximately 150 resentencing, pretrial, sentencing, and habeas proceedings to support victims who couldn’t look to prosecutors in their case, for assistance during the administration, which ended last month, of then-District Attorney George Gascón

Now, after 31 years as a deputy district attorney and four years as a pro bono victims-rights lawyer, she will be returned to the District Attorney’s Office last Monday. The new head of that office, Nathan Hochman, has recruited her as director of the Victim Witness Division.

Gascón, on his first day in office—Dec. 7, 2020—issued several “special directives” which Hochman, on his own first day at the helm, last Dec. 3, rescinded. Among the most troubling of Gascón’s decrees, to Cady, was that prosecutors, in contrast to what had been the practice for decades, were barred from attending parole hearings. In the past, deputy district attorneys often put forth arguments on behalf of the family as to what they felt justice required.

When she was a prosecutor in the pre-Gascón days, Cady says, the office mantra had been: “This may be your case, but for the victims, it’s their life.” She expresses the view that Gascón’s directive “completely abandons victims at parole hearings,” adding:

“This is horrible enough for murder victims’ families, but for rape victims, it is beyond cruel to put them in the position of attending a parole hearing alone when the inmate has an attorney.”

Cady did something about it, proceeding to represent about 50 persons—sex crime victims or family members of murder victims—at parole hearings.

Sentencing Hearings

She also acted on behalf of victims and family members at sentencing and resentencing hearings—often in tandem with former Los Angeles County District Attorney Steve Cooley and, until his death in 2023, retired Deputy District Attorney Brentford J. Ferreira.

|

|

|

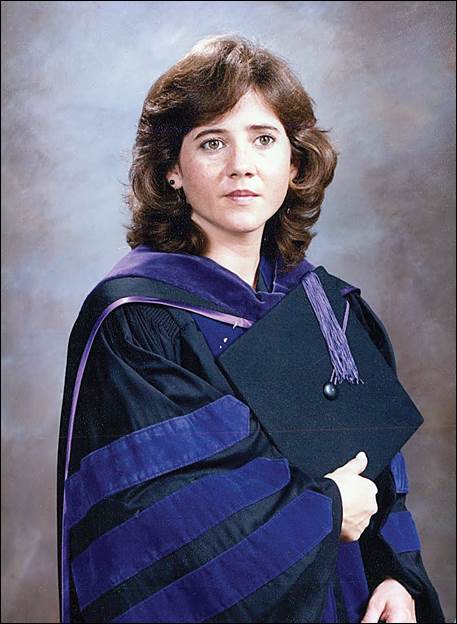

Cady is seen at her graduation from Southwestern Law School, in 1989. |

Under Art. I, §28 of the California Constitution, as amended in 2008 by Proposition 8—known as “Marsy’s Law”—certain rights are provided to “victims of crime and their families.” The rights include “reasonable notice of all public proceedings, including delinquency proceedings, upon request, at which the defendant and the prosecutor are entitled to be present and of all parole or other post-conviction release proceedings and to be present at all such proceedings.” Also conferred on victims and families is the right “[t]o be heard, upon request, at any proceeding, including any delinquency proceeding, involving a post-arrest release decision, plea, sentencing, post-conviction release decision, or any proceeding in which a right of the victim is at issue.”

But not expressly accorded victims and their families is standing—although Cady has argued that, in some contexts, that status is implicit in Marsy’s Law.

‘Assertion of Rights’

She relates that certain rights under Marsy’s Law are available only “upon request” and says that “to let the court know that the victims are requesting all their rights,” she filed a “Notice of Appearance and Assertion of Rights” in several cases where Gascón’s office was siding with the position of a defendant, noting:

“I have not had a judge not allow me to file this document.”

But given the lack of recognized party standing for those she represents—and despite the lack of authority for the filing of amicus briefs in a trial court—she generally asked that her filing be so regarded.

Several judges have done so.

One such jurist is Los Angeles Superior Court Judge George G. Lomeli. He agreed with the lawyer for an inmate, Jesse Gonzales, who was convicted in 1979 of the murder of a sheriff’s deputy and sentenced to death, that the family of that victim had no standing to put forth legal positions as to why a habeas corpus petition should not be granted. However, he treated Cady’s filing as an amicus brief.

The Office of District Attorney was conceding that there had been a Brady violation—a failure of the prosecution to turn over to the defense exculpatory matter—but Lomeli, aided by Cady’s argument, denied relief.

Unexpected Role

Cady had not planned on becoming a victims’ rights advocate upon her retirement as a prosecutor. She and her husband—John Pomroy, a retired detective for the Pomona Police Department—wanted to see the U.S. with their daughter before she started high school, so they packed their necessary belongings and hit the road in a motorhome. The family made it to 35 states before the COVID-19 pandemic struck and they came home to Los Angeles. At the time, Cady intended to devote her time to her roles as wife and mother.

But everything changed when Gascón took office.

Cady says that on Gascón’s first day in office, she “started getting calls” from prosecutors who were alarmed by the special directives.

New policies went far beyond barring attendance at parole hearings. Gascón declared that “sentence enhancements or other sentencing allegations, including under the Three Strikes law, shall not be filed in any cases and shall be withdrawn in pending matters.” He proclaimed that deputies were never to seek the death penalty, could not request cash bail for certain minor offenses and would agree to the release for those currently awaiting such bail, and would end the charging of minors as adults. Gascón also announced plans to establish a resentencing unit to seek the early release of potentially thousands of inmates, and to reopen several cases of officer-involved shootings that had been declined for filing.

Decides to Act

Believing that the new policies would “negatively impact victims” and hamper deputy DAs “in their ability to do their job,” Cady decided that she needed to take a part in attempting to topple the new district attorney.

Although a campaign to recall Gascón had been launched by amateurs within a week of his taking office and quickly fizzled, Cady co-chaired a second effort, which was heavily funded and supported by professional political consultants. It failed to garner the necessary number of signatures to qualify the recall for a vote—or so the Office of Registrar-Recorder announced.

It was alleged in ensuing litigation that huge numbers of signatures had been wrongly rejected and that the number of needed signatures, supposedly 566,875—based on 10% of the registered voters in the county—was exaggerated because persons no longer eligible to vote were included in the figure The lawsuit was dropped after delays made it clear that nothing would be gained by it owing to the closely approaching election.

But, from Cady’s perspective, her work in the recall campaign was not fruitless. It brought her into contact with Glendale attorney Sam Dordulian, of the Dordulian Law Group, who extended an offer to her to serve of counsel to his firm. She accepted. That gave her, she says, “the ability to have letterhead and malpractice insurance,” expressing gratitude to Dordulian for lending her those advantages.

Described as ‘Godsend’

Dordulian, in turn, says that having Cady as part of the firm was “a godsend.”

He explains that his firm’s investigator was a former Los Angeles police officer and the investigator’s friends, who were still on the force, were referring crime victims to the firm for help. Dordulian, a former deputy district attorney, says he felt he had to get involved because the victims were “desperate” for guidance and support.

After the firm received some media coverage for its victim advocacy, Dordulian recounts, the number of calls the firm was getting became “overwhelming.” He spent more than two weeks handling nothing but such advocacy cases, which was not sustainable for the firm, and “that’s when Kathy came around.”

Dordulian recalls that Cady “was willing to jump on board and take everything on,” which, he says, “helped me out tremendously.” Cady “woudn’t say ‘no’ to anyone or anything” relating to victims’ rights and she has been “tireless” in her advocacy, Dordulian says, remarking:

“Once she took over, I didn’t look back, and she’s been incredible.”

Cady “works tirelessly, and she really believes in the cause, and believes in the victim,” Dordulian says. That, in his view, “makes her incredibly powerful” as an advocate.”

Working With Victims

After signing on with Dordulian’s firm, Cady began to meet with victims and family members of slain victims, trying to make sure they were heard and their constitutional rights were protected.

These persons are entitled to an explanation of charging decisions, Cady contends, and even if the they disagree, at least they will understand the bases—it “feels like being abandoned, like what happened to them was not important,” she says.

Many victims reached out directly to her, she reports, although the role she played was different from that of a prosecutor. Given that she was not with the District Attorney’s Office, she did not have access to all the facts of any given case, but she did not always need to know them.

“What I hear from the victim is the pain and anguish and trauma of what they’re going through,” Cady says, and there’s no need to victimize the person anew by having him or her relive the crime by talking about it.

“I also don’t come in with an agenda on ‘Here’s what we need to do,” Cady says. “It’s more about, ‘I’m sorry you went through that, what do you want to have happen now?’ ”

Cady says it is important for victims “to know what is going on, to know what their rights are, and to help them assert those rights.” Her biggest job was “managing expectations,” but she says that with most victims, “as long as they know they have tried and done everything they can, they can handle pretty much any outcome.”

1980 Conviction

One of her most recent efforts was opposing the resentencing of Ricardo Rene Sanders, convicted in 1980 of murdering four persons at a Bob’s Big Boy restaurant and sentenced to death. In his 1985 opinion upholding the convictions, Justice Stanley Mosk (now deceased) remarked that “the crimes were brutal.”

A hearing is scheduled for later this month.

That’s one project she’s been obliged to drop in light of her new post. She explains:

“Essentially, over the last four years I have usually come in to represent victims when the assigned DDA was precluded from doing that because of some Gascón policy. Now that Nathan Hochman is following the law—not policy—and basing decisions on the facts, etc., individual representation of victims is no longer as important.”

As a deputy district attorney, Cady notes, she “can no longer represent victims,” requiring her to file notices of withdrawal in cases in which she has done so.

“I will not represent the DA’s Office in any case in which I represented the victim and will likely be ‘walled off’ to avoid any appearance of impropriety or bias,” she relates.

Other Activities

Cady has also advocated for victims’ rights through legislation, writing articles lambasting Gascón’s policies, filing amicus briefs, working with nonprofits, and engaging in litigation.

She currently serves on the board of directors for the Children’s Advocacy Center for Child Abuse Assessment and Treatment, and on the advisory committee for the Children’s Advocacy Centers of California, the state chapter of the National Children’s Alliance. Cady is also part of the National Crime Victim Law Institute and is an honorary advisory board member of Justice for Homicide Victims.

As of late last year, Cady was involved in a lawsuit against the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation and Board of Parole Hearings, serving as co-counsel with the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation in representing a rape victim in challenging Penal Code §3051’s provision of a parole hearing for the perpetrator.

The rapist was sentenced to 50 years in prison, but because of his youth at the time of the crime, he became eligible for a parole hearing in October. Cady attended the hearing with the victim. The perpetrator was denied parole, but he’ll have another shot in the spring of 2026 unless Cady and her allies prevail on their argument that he never should have been eligible for parole in the first place.

“If we win, it could have consequences for sex crime victims statewide,” Cady says.

Drafts Bills

Cady has also drafted legislation and testified in Sacramento regarding the bills. They concerned victims’ rights and child abuse.

Four of her bills were carried by legislators and were enacted into law. Through her efforts, a prosecuting witness in human trafficking or a child pornography case may now be accompanied while testifying by a “support person” and by a trained and certified “facility dog” or “therapy dog” and a child who testifies in a case involving a serious felony may also have such a dog present.

Adverse employment actions may now not be taken against crime victims who take time off from work to attend criminal or juvenile delinquency proceedings relating to the offenses against them, and protective orders may be secured by victims and by witnesses of crimes.

Efforts Draw Praise

Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Daviann Mitchell, a fellow 2024 MetNews Person of the Year, hails Cady as “very passionate, very smart, and very committed to victims” both in her former capacity as a prosecutor and “especially now” as an advocate, “giving victims an opportunity to be heard and have a voice, and not letting them be forgotten.”

Former Los Angeles District Attorney Steve Cooley says that in his 50 years of practice, he “can say with confidence there is no one out there who is a greater and better victim advocate than Kathy Cady.”

Cooley, who was himself heavily involved in the effort to recall Gascón, says that Cady’s leadership “inspired many others to join in that cause.”

Cady, has “made innumerable court appearances fighting against Gascón’s effort to reduce sentences or to change previous jury verdicts obtained by previous” deputy district attorneys and “this advocacy on her part has generated huge praise from scores of next-of-kin of murder victims whom she represented in court and in other hearings,” he comments.

Cooley declares he “cannot think of any person more deserving of the Person of the Year Award” than Cady “based upon her sheer unwavering and selfless commitment to victims, the next-of-kin of murder victims and the law-abiding public.”

Prosecutor’s Perspective

Deputy District Attorney Pak Kouch says Cady, whom she’s known for more than 20 years, “has always been so dedicated and passionate about her work.”

Cady had been her supervisor for a time and Cady “led by example,” always being “the first one in and the last one out,” Kouch recalls.

She says she thinks Cady’s advocacy work “stems from her person” because “it’s just in her DNA,” characterizing Cady as “incredibly compassionate.”

Kouch also cites reliability as one of Cady’s assets, remarking:

“If she says she will be there, she will be there, and she will fight for you, whoever you are.”

There was a retirement party for Cady and, she remembers, “we were all saying this is the beginning of something different and something new.” But instead of retiring, Kouch says, Cady has “continued to be fierce, and fearless, in fighting for what’s right, against all the odds.”

Donna Wills, a retired deputy district attorney who supervised Cady at the Bureau of Victim Services, says Cady is “one of the most dedicated persons I have ever come across.”

Cady is “innately motivated to help others,” Wills says, bringing to mind:

“She told me one time her father told her if she didn’t have any work to do, she’d figure out a way to find some work, and that’s exactly what she did.”

Malinda Wheeler, a forensic nurse and a founding board member of the Children’s Advocacy Center, says Cady’s “energy level and knowledge and passion is just unmatched by anyone else I know.” Cady “never gives up,” Wheeler says.

Hanisee’s Observations

Deputy District Attorney Michele Hanisee, president of the Association of Los Angeles Deputy District Attorneys, says that what she has noticed in the 20-plus years that she has known Cady is that she “has a great deal of compassion and sensitivity” for others. Cady had been her supervisor in the Victim Impact Unit, and Hanisee says she “has an innate ability to connect with victims” and “has always been a wonderful advocate for victims of crime.”

Cady is “willing to bend over backwards to help,” and it is not unusual for her to be up until the wee hours of the morning writing briefs or whatever else is needed, Hanisee says. In her assessment, Cady is “really a superhero and so deserving” of recognition for that.

In like vein, Deputy District Attorney Shawn Nicole Randolph says Cady “needs a superhero cape,” explaining:

“I don’t know anyone who has done more for victims of crime, truly hands down.”

In her experience, Randolph observes, “there’s no one like her,” in the courtroom and in the political arena. “You can’t not listen to her, and you can’t say ‘no’ ” because “she just won’t take ‘no,’ but in a way that’s kind, and not pushy.”

Cady “has a way of advocating for victims of crimes that is as tenacious as I’ve ever seen,” but “always professional” and “always with a smile,” Randolph says. “That’s a kind of skill you don’t really see in many people.”

Patricia Wenskunas, the founder and CEO of Crime Survivors, says it is “an honor and a privilege to not only collaborate with Kathy, but to also call her a friend.” Wenskunas recalls Cady was “open arms to collaborate and partner together” two decades ago, when she was still a prosecutor, and she has remained “a woman of passion, purpose, commitment and dedication.”

Cady “cares deeply for those that we serve,” and “it is absolutely remarkable how many she has helped,” Wenskunas opines. “She’s a small but mighty woman.”

Los Angeles-Born

This diminutive dynamo was born and reared in the San Gabriel Valley. Her mother died when she was seven years old, but she gained a “second mom” when her father remarried.

Before immigrating to the United States and marrying Cady’s father, Cady’s stepmother had been an attorney in Holland. Her stepmother did not resume the practice of law after arriving in the U.S., focusing instead on bringing up Cady and her younger brother, plus an additional three children born into the family.

Cady’s father was an accident reconstruction engineer, and two of Cady’s brothers followed in his footsteps by going into engineering.

As a child, Cady says, she didn’t expect to be an attorney. In fact, she recounts, she wasn’t sure what she wanted to be when she grew up. Cady was active in choir and theater.

She chose to go to the University of California at Davis where she majored in political science. Her coursework included a class on constitutional law, and Cady says she found it fascinating.

|

|

|

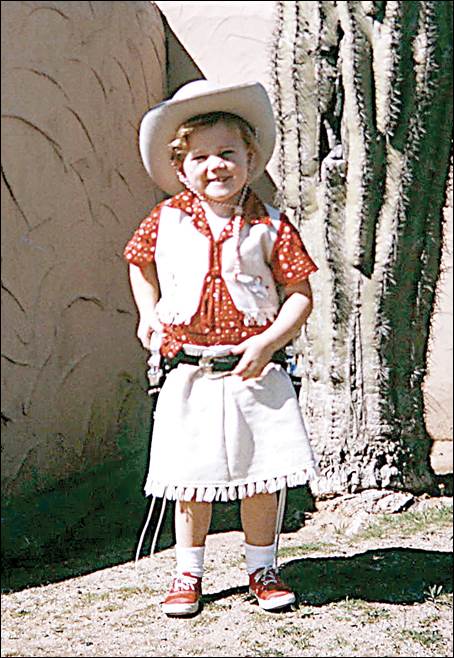

Pictured here is young Cady dressed up as a cowgirl. |

“I could hardly wait for the next class each time, I just loved it so much,” she recalls. “I think that’s what solidified for me that I wanted to go to law school.”

After a few years of prosecuting cases, Cady joined the office’s Bureau of Victim Services. Cady hadn’t sought out the post, but she “happened to be in the right place at the right time,” and it turned out to be a perfect fit for her.

It was a “pivot” from trial work, as it mostly involved providing training to the other attorneys in the office, but she recalls she found she enjoyed being able to work directly with the victims of crimes.

Little would she have imagined then that, years later, after retiring as a deputy D.A., she would become the county’s foremost advocate of victims’ rights, drawing nationwide attention.

All of the work she did during the Gascón regime took an emotional toll on her. Cady relates that she often keeps the Hallmark Channel playing on the television set to avoid seeing “the evil that’s out there,” reflected on the news.

She notes that she relishes the company of her husband, her daughter, her two sons, and her granddaughter. And, there are the two family dogs: Duchess, a Doberman who was born at Inland Valley Animal Shelter and Abigail, is a poodle mix adopted from Pasadena Humane Society.

Copyright 2025, Metropolitan News Company