Page 1

S.C. Reverses Conviction, Sentence of Alleged Serial Killer

Opinion Says Trial Judge Erred in Removing Juror During Guilt-Phase for Anti-Prosecution Bias, Failure to Deliberate in Case Against Gang Leader Known as ‘Monster of Atwater Village’

By Kimber Cooley, associate editor

|

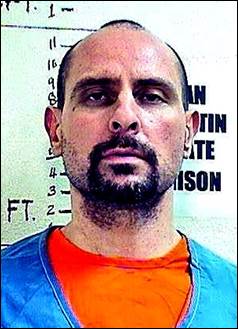

TIMOTHY MCGHEE inmate |

The California Supreme Court yesterday reversed, in a unanimous decision authored by Justice Goodwin H. Liu, the murder convictions and death sentence of a gang leader known for boasting in rap lyrics about the pleasure he felt in killing, finding that a guilt-phase juror was improperly removed during deliberations based on other panelists expressing concern that the man held anti-prosecution bias and was irrationally locked-in to his point of view.

Timothy McGhee, a high-ranking member of the Toonerville street gang, was convicted of three counts of murder and four counts of attempted murder for string of shootings occurring between October 1997 and November 2001 in the northeastern Los Angeles neighborhood of Atwater Village, including an ambush on police officers who were in pursuit of other suspects. After his trial, a jury also found true two special circumstances.

Police and prosecutors described the defendant as a thrill killer and one of the most feared members of the Toonerville crew. News reports at the time referred to McGhee as “the Monster of Atwater Village.”

Although ballistic evidence and other witnesses were presented, most of those testifying against McGhee were either former gang members, including accomplices in the killings, had extensive criminal histories, or admitted to using alcohol or drugs before observing the events at issue.

Jury Deliberations

At the end of the third day of deliberations in the guilt phase of McGhee’s trial, then-Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Robert J. Perry (now retired) received a note from two panelists saying:

“We, Jurors Number Nine and 11, feel that the majority of the jury feels as though one juror, Number Five, has been swayed and is not capable of making a fair decision in any of the counts against McGhee.

“Juror Number Five is using speculation as facts and has no rational explanation as to why he feels the way he does other than saying every prosecution witness was coached and lying. Yet the defense witnesses are all telling the truth and believable.”

Perry questioned the panelists, and all but three—not counting the singled-out juror—expressed concern over Juror Five. Some accused him of being biased against the prosecution or police, and others said he was locked into his point of view, did not deliberate with the rest of the group, and tended to be “irrational” in his thinking.

Juror 11 said Juror Five was “using speculation as facts,” had indicated that he “wasn’t prone to accept anybody’s testimony from the prosecution because everybody has convictions,” and had expressed that he “doesn’t like the cops in this case.” Juror Five had also purportedly told the rest of the panel that “I am not changing my mind.”

When questioned, Juror Five commented that he felt that a “wave” of concerns from one or two panelists was unfairly sweeping the panel.

Perry removed the juror, noting that “I am well aware that the Supreme Court has told us, the fact that a juror does not deliberate well or relies upon faulty logic or analysis does not constitute a refusal to deliberate,” but concluded that the totality of the evidence supported a view that the panelist had strong anti-prosecution bias and showed a failure to deliberate.

After an alternate was appointed to the panel, a guilty verdict was returned on all charges and special circumstances.

Perry sentenced McGhee to death in 2009. Perry said the then-35-year-old treated killing “as some kind of perverse sport, as if he was hunting human game” and found that there was compelling evidence of McGhee having been involved in the murders of Ronnie Martin, who was shot to death in 1997, Ryan Gonzalez, who died in 2000, and Margie Mendoza, who was killed in 2001.

The case reached the high court on automatic appeal.

Jury Right Implicated

Liu noted that “[b]ecause the discharge of a deliberating juror implicates a defendant’s jury trial and due process rights under the federal and state Constitutions,” the standard of review is less deferential. He wrote:

“To uphold the discharge of a juror,…a reviewing court ‘must be confident that the trial court’s conclusion is manifestly supported by evidence on which the court actually relied,’ considering that evidence and the court’s reasons for discharging the juror in light of the entire record.”

He turned to the two bases cited by Perry for the discharge of Juror Five—failure to deliberate and anti-prosecution bias or prejudice against police. As to the first basis, he explained that case law makes clear that it is only shown where a juror refuses to deliberate and said that “[e]xamples…include refusing to engage in dialogue at all, rejecting arguments out of hand, and physically distancing himself or herself from the group.”

Liu noted that the main defense strategy at trial was to attack the credibility of witnesses, based on some admitting to receiving leniency on their own criminal cases and others saying the police coached them by pointing to McGhee’s image in photographic lineups, and opined that “[t]he trial evidence concerning the credibility of these key witnesses bears on the controversy surrounding Juror No. 5’s views.”

Finding that Juror Five’s conduct did not rise to this level of obstinacy, he wrote:

“[T]he record shows that Juror No. 5 had been engaging with fellow jurors but that he was refusing to change his mind….

“….Juror No. 5 shared with his fellow jurors the reasons for his view of the prosecution’s evidence….[H]e did not think gang members would testify against one another, that he did not believe witnesses with convictions, that he did not like the police ‘in this case,’ and that he thought witnesses were pressured to accept a deal with the prosecution or police.”

Anti-Prosecution Bias

The jurist remarked:

“The question of bias in this case turns not on a common understanding of the word but on a more precise definition, which focuses on whether the juror’s judgment or beliefs about an issue are untethered to the facts presented at trial…. The question is not simply whether a juror’s views derive from a personal leaning or inclination for or against one side, but rather whether the juror’s views and conclusions are based on specific evidence presented in the case.”

Applying that standard, he said:

“The specific accusations of bias against Juror No. 5 that the court credited were not well-founded, relied on the opinion statements of other jurors, and did not manifestly support the court’s discharge decision. To support their view that Juror No. 5 was biased, several jurors cited Juror No. 5’s belief that the prosecution witnesses were not credible because they had prior convictions.”

Finding this to be an oversimplification of the reasons behind the panelist’s alleged distrust of the witnesses, he wrote:

“The record discloses any number of permissible grounds, in addition to prior convictions, on which Juror No. 5 could have questioned and, according to several jurors, did question the credibility of the prosecution’s witnesses. Evidence elicited from both the prosecution and defense showed that many of the witnesses who implicated McGhee in the shootings were present or former gang members….Moreover,…the defense introduced evidence from which it could be inferred that several witnesses had been coached by detectives before implicating McGhee.”

He added:

“[T]he trial court concluded that Juror No. 5 had ‘a strong anti-prosecution bias’ without carefully examining whether Juror No. 5’s belief that the prosecution witnesses were lying was a plausible inference from the evidence presented. In fact, Juror No. 5’s views largely aligned with the defense evidence in this case.”

The case is People v. McGhee, 2025 S.O.S. 954.

Copyright 2025, Metropolitan News Company