Page 1

Ninth Circuit:

Failure to Raise ‘Obvious’ ‘Winner’ Argument Constituted Ineffective Assistance of Counsel

Opinion Says Failure to Argue in Suppression Motion the Well-Established Rule Against Curtilage Invasion, Without Warrant, Fell Below Standard of Practice

By Kimber Cooley, Associate Editor

|

|

|

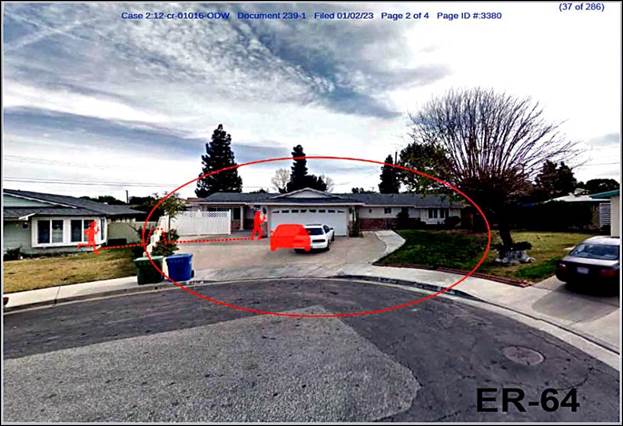

A Ninth Circuit panel yesterday explained, in text above the illustration: “The following depiction overlaid on a photograph of the house shows the path the deputies took to approach the garage….[T]he garage entrance was fully exposed from the sidewalk and no more than 1½ car lengths from the sidewalk.” |

The Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals yesterday held that the failure of defense counsel to argue during a suppression motion that police violated his client’s Fourth Amendment rights by invading the curtilage of his home without a warrant—in hopping a neighbor’s fence and sneaking up from the side to view into the open garage from about one foot away—amounted to ineffective assistance of counsel warranting vacatur of the sentence.

Challenging their sentences were Harson Chong and Tac Tran, who were convicted of federal drug and gun charges following the search of Chong’s home in July 2012. Before obtaining a search warrant, deputies with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department observed Tran—a parolee under surveillance due to suspected narcotics activities—enter Chong’s home.

After Deputy Choong Lee observed Tran with suspected drugs in the garage, a search warrant was secured and large amounts of ecstasy, methamphetamine, cocaine, and marijuana were found in the house as well as guns and digital scales. Chong and Tran were charged with federal drug and gun charges.

Both defendants filed motions to suppress the evidence on Fourth Amendment grounds—but failed to assert that the deputies trespassed onto the curtilage of the home without a warrant—and the motions were denied.

After their convictions were affirmed on direct appeal, Chong and Tran moved for post-conviction relief under 28 U.S.C. §2255 based on ineffective assistance of counsel.

District Court Judge Otis D. Wright II of the Central District of California denied the motions.

Wright Reversed

The Ninth Circuit panel—consisting of Circuit Judges Daniel Aaron Bress and Patrick J. Bumatay and Senior District Court Judge Robert S. Lasnik of the Western District of Washington, sitting by designation—reversed the denial as to Chong in a per curiam opinion.

The panel affirmed the denial as to Tran, finding no ineffective assistance because Tran lacked standing to challenge the search as he had no expectation of privacy in someone else’s home.

Bumatay “fully” concurred in the opinion but wrote separately to emphasize the seriousness of the constitutional violation.

Chong was represented in the suppression motion by Charles Kelly Kilgore, a Beverly Hills defense attorney and adjunct professor at Pepperdine University’s Caruso School of Law. Tran was represented by Kim Savo and Lisa LaBarre of the Federal Public Defender’s Office.

Curtilage of Home

The panel noted that the core of the Fourth Amendment’s protection against unreasonable searches and seizures is the idea that a person has the right to retreat into the privacy of his or her home without unreasonable government intrusion. They said that “[t]his protection extends beyond the walls of the home” and that the curtilage, or area immediately surrounding the house, is also protected against warrantless searches.

The judges reasoned that Chong’s ineffective assistance of counsel claim “turns on whether the sheriff’s deputy was standing within the curtilage of Chong’s home when he saw Tran throw the drugs, and why he approached the home to get into that position.”

Turning to the facts of the case, they wrote:

“A sheriff’s deputy crossed over a neighbor’s retaining wall and traversed the driveway toward the garage entrance, taking a route about halfway up the driveway to the home and not near the sidewalk. As the deputy approached the open garage door, he observed Tran drop a clear plastic baggie containing methamphetamine. At the time he saw this, the deputy was standing directly to the left of the open garage door and, by his own testimony, only about one foot from the garage threshold.”

The jurists continued:

“Here, under any conception of curtilage, one foot from the garage door entrance of a single-family home on a residential street is surely within the curtilage of that home. While the driveway wasn’t enclosed, the officer’s close proximity to the garage door entrance here more than makes up for that.”

Method of Approach

The panel further found that the method of Lee’s approach violated Chong’s Fourth Amendment rights not just under the curtilage analysis—inherited from common law trespass doctrine—but also under an inquiry as to whether Chong had a reasonable expectation of privacy in the activities in his open garage. Wary of the approach Lee made, they said:

“He didn’t walk up from the sidewalk, where he would be spotted immediately and from where guests typically enter the property. Instead, the deputy jumped the side-retaining wall of the house, hugged the front side of the house (likely to keep out-of-sight of anyone in the garage), and suddenly appeared a foot away from the open garage door. Such an approach to the threshold of the garage, late at night, would certainly surprise any person in the garage, like Tran here. Just because the garage entrance was exposed to the public for a period doesn’t give law enforcement license to treat it as a public thoroughfare.”

The panel concluded that “[b]ecause the exclusionary rule would have been appropriate for all this evidence” as fruit of the warrantless search by Lee, there is a reasonable probability that the verdict would have been different had Kilgore raised the issue.

Ineffective Assistance

In order to prevail on an ineffective assistance of counsel claim, the defendant must show that his lawyer’s performance fell below an objective standard of reasonableness and that the deficient performance prejudiced his defense. Turning to the facts of the case before them, they wrote:

“As we have already established, if a motion to suppress was brought by Chong’s counsel arguing that the sheriff’s deputy violated the Fourth Amendment when he observed Tran throw the baggie of drugs, it would have succeeded and it would have resulted in the exclusion of the fruits of that search. Chong’s counsel also states he had no ‘strategic, tactical, or legal decision’ in failing to make this motion.”

The judges said that “[t]he curtilage argument should have been well-known” to Kilgore and declared:

“We conclude that Chong’s counsel’s representation fell below an objective standard of reasonableness….While we do not evaluate counsel’s performance with perfect 20/20 hindsight,…the curtilage argument here was not merely a winner but an obvious argument that counsel clearly should have made.”

As to Tran, they wrote that “strategic reasons existed for distancing Tran from Chong’s home” as any argument that Tran had standing to object to the officer’s invasion of the curtilage of the home would risk a finding that a search of the home was proper as a parole search of Tran’s property. They commented that “[t]hat type of judgment call is not deficient performance.”

Bumatay’s Concurrence

Bumatay said:

“Few things are more serious than an overstep of government power. And here, we have a literal one. When law enforcement officers entered the property adjoining the defendant’s house at night, jumped the neighbor’s side retaining wall, crossed the defendant’s front yard along a partially fenced-off front porch, and arrived just one foot away from the open garage door of the defendant’s private home—all without a warrant—they crossed a line. And that line was real.”

He opined:

“[T]he government counters that the common-law trespass thread of the Fourth Amendment is a relatively new phenomenon and so it was excusable for Chong’s counsel to miss it. But that’s wrong….[P]rotection against trespassing on curtilage is deeply rooted in our nation’s history. So it should have been obvious even before more recent Supreme Court cases’ articulation of the Fourth Amendment right.”

The case is Chong v. U.S., 23-55140.

Copyright 2024, Metropolitan News Company