Page 3

Ninth Circuit:

Suit Alleging Deceptive Huggies Labels Partially Reinstated

Ninth Circuit Panel Says Reasonable Consumer Could Read Label as Promise of No Synthetic Ingredients

By a MetNews Staff Writer

|

|

|

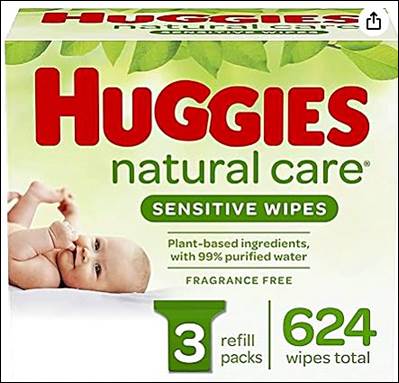

Depicted above is a package of Huggies “natural care” baby wipes. The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals yesterday partially reinstated a consumer action claiming false labeling |

A reasonable consumer could interpret unqualified “plant-based” and “natural” labels on baby wipes as unambiguously representing that the products do not contain synthetic ingredients, the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals held yesterday.

The question arose in a class action alleging that several versions of Huggies-brand baby wipes are deceptively marketed in violation of California law. The court divided the products into two classes—those with an asterisk after the label with the corresponding qualifying statement “*70+% by weight” and those with no qualifier—and found that the complaint states a false advertising claim as to the wipes with no limiting description.

The appellate court further held that when language on the front of the packaging is unambiguous—such that a reasonable customer would view it as having only one meaning—a court may not consider at the pleading stage ingredient lists on the back of the item to determine whether the advertising is misleading, clarifying Ninth Circuit precedent.

Circuit Judge Ronald M. Gould authored the opinion affirming the dismissal by District Court Judge Jesus G. Bernal of the Central District of California, for failure to state a claim under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 12(b)(6), as to the products containing labels with asterisks and reversing the dismissal as to the wipes with the unqualified labels.

Circuit Judge Salvador Mendoza Jr. and Senior Sixth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Ronald Lee Gilman, sitting by designation, joined in the opinion.

False Advertising Claims

Appealing the dismissal was Summer Whiteside who filed a putative class action against Kimberly Clark Corp. in November 2022 alleging deceptive marketing under California’s Unfair Competition Law, False Advertising Law, and Consumer Legal Remedies Act.

The complaint alleges that the words “plant-based” and “natural” on the front labels of the baby wipes suggest that the products do not contain synthetic ingredients. The wipes contain a list of ingredients on the back of the packaging, which contains the words “natural and synthetic ingredients.”

On June 1, 2023, Bernal dismissed the complaint in its entirety, writing:

“[T]here is no deceptive act to be dispelled because Defendant’s packaging is accurate. Plaintiff does not dispute that the Products, with or without the asterisk, in fact contain at least 70% plant-based ingredients by weight. As such, Defendant’s use of the term ‘plant-based’ even on Unasterisked Products is not misleading because it is truthful. ‘Plant-based’ reasonably means mostly derived from plants, which is what these Products are.”

Reasonable Consumer Standard

Gould noted that false advertising claims are governed by the “reasonable consumer” standard requiring a plaintiff to show that a significant portion of the public could be misled by the defendant’s marketing claims and that “[p]lacing a disclaimer or a fine-print ingredients list on a product’s back label does not necessarily absolve a defendant of liability for deceptive statements on the front label.”

The jurist said:

“A threshold issue in this case is whether the Products’ back-label ingredients list—which states that the Products contain ‘natural and synthetic ingredients’—should be considered at the pleadings stage. The parties generally agree that if the front label is ambiguous, then we must look to the back label. But the parties disagree on how we may determine that the front label is ambiguous, and they present us with two theories.”

Kimberly Clark asserts that a front label is ambiguous if it can have more than one possible meaning while Whiteside contends that wording with two possible meanings can be unambiguous for Rule 12(b)(6) purposes if the plaintiff plausibly alleges that a reasonable consumer would view it as having one explanation.

The court agreed with Whiteside’s construction of the law but acknowledged that the 2023 Ninth Circuit case of McGinity v. Procter & Gamble Co. “lends some facial support to Defendant’s position.”

McGinity Case

In the McGinity opinion, also authored by Gould, the court held that “the front label must be unambiguously deceptive for a defendant to be precluded from insisting that the back label be considered together with the front label.”

Gould said the court will “take this opportunity to clarify our analysis” in McGinity, declaring:

“[W]e did not hold that a plaintiff must prove that the label is unambiguously deceptive to survive dismissal. After all, that position would be manifestly incompatible with the pleading standard found in FRCP 12(b)(6). Rather, we held that a plaintiff must plausibly allege that the front label would be unambiguously deceptive to an ordinary consumer, such that the consumer would feel no need to look at the back label.”

He added that the defendant’s interpretation of McGinity “would effectively overrule” earlier Ninth Circuit precedent that “require[s] only that a front label be plausibly misleading for a plaintiff to survive dismissal” and McGinity did not hold otherwise as that would be “something we…could not do as a three-judge panel of the Ninth Circuit.”

The jurist concluded:

“[A] front label is ambiguous when reasonable consumers would necessarily require more information before reasonably concluding that the label is making a particular representation. Only in these circumstances can the back label be considered at the dismissal stage.”

Unambiguous Representation

Applying the standard to the products with unqualified labels, he wrote:

“Plaintiff has plausibly alleged that a reasonable consumer could interpret the front label as unambiguously representing that the Products do not contain synthetic ingredients, and that a reasonable consumer would not necessarily require more information from the back label before so concluding. These plausible allegations preclude Defendant’s reliance on the back-label ingredients list at this stage.”

Gould was unpersuaded by Kimberly Clark’s contention that a reasonable customer knows that baby wipes are manufactured through sophisticated processes, using synthetic ingredients. He wrote:

“Reasonable consumers also understand that meat does not grow on trees, yet technology has advanced such that plant-based meat is now available. Consumers could reasonably suppose that manufacturers have similarly devised a way to make baby wipes using only plant-based compounds.”

The judge remarked that the Federal Trade Commission’s publication “Guides for the Use of Environmental Marketing Claims” (referred to in the opinion as “Green Guides”) supports the court’s conclusions. The publication warns that “unqualified representations like ‘made with renewable materials’ are likely to mislead a reasonable consumer to believe that a product ‘is made entirely with renewable materials.’ ”

He declared that “this is not one of the ‘rare’ cases in which dismissal is appropriate.”

Asterisked Labels

Turning to the labels with the qualifying statement “*70+% by weight,” he remarked that “[t]he Asterisked Products are not an exact match for the example in the Green Guides, but they are consistent with the principle illustrated therein that environmental claims must be qualified.”

He added:

“We reach the same conclusion even giving Plaintiff the benefit of the doubt that ‘70%+ by weight’ is ambiguous. If the statement were ambiguous, a reasonable consumer would require more information from the back label, and the back label clarifies that the Products contain both ‘natural and synthetic ingredients.’ ”

Gould reasoned that “[e]ven before reading the back label, the presence of an asterisk alone puts a consumer on notice that there are qualifications or caveats, making it unreasonable to assume that the Products were 100% plant-based.”

He noted that Bernal dismissed the plaintiff’s claims for warranty and unjust enrichment and added that “the district court must reconsider Plaintiff’s warranty and unjust enrichment claims” concerning the products with unqualified labels.

The case is Whiteside v. Kimberly Clark Corp., 23-55581.

Copyright 2024, Metropolitan News Company