Page 3

Court of Appeal:

Home Owned by Kathryn Grayson Remains City Landmark

Justices Reject Contention That Inadequate Notice Was Given of Public Hearing on Designation

By a MetNews Staff Writer

|

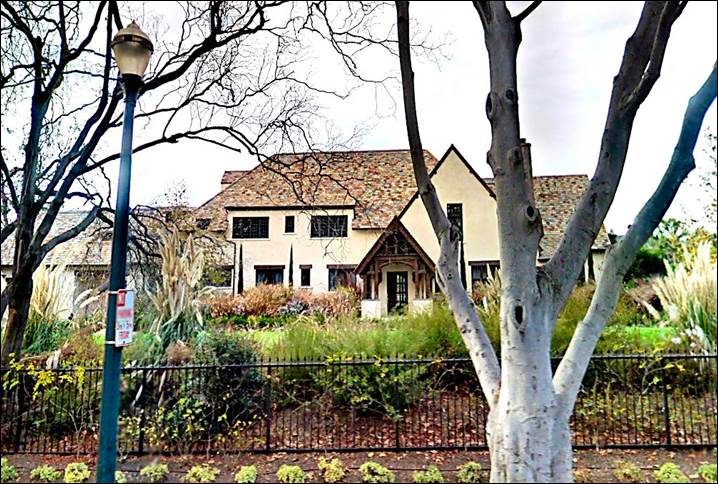

Depicted is a mansion in Santa Monica located near the Riviera Country Club. The Court of Appeal for this district has rejected a challenge to the procedure used in designating the home a city landmark. |

The 1926 Santa Monica mansion that was occupied for 65 years by actress/singer Kathryn Grayson will remain a city historic landmark, the Court of Appeal for this district has decided, rejecting the current owner’s contention that a lack of public notice of the 2010 hearing at which the11,000-square-foot home was so designated requires that the action must be invalidated on due-process grounds.

Acting Presiding Justice Judith Ashmann-Gerst of Div. Two authored the an unpublished opinion, filed Tuesday.

Grayson had resided in the house from 1945 until her death on Feb. 17, 2010. It was purchased by personal injury attorney Otto L. Haselhoff in 2018 for $16 million, and on May 7, 2019, he filed suit in the Los Angeles Superior Court against the city and 250 Does seeking to remove the landmark status which places restrictions on modifications to the property.

Haselhoff’s Contentions

“The City is well aware of the draconian impact of its Landmarks regulations,” Haselhoff asserted, elaborating:

“The defendants’ unlawful Landmark designation freezes the property in its current configuration, design and appearance. Local law effectively forbids replacement or meaningful alteration of the building. At all times since the filing of the Landmarks Commission’s application. Petitioner has been forbidden to make any unauthorized changes to the property, with the result being that the full use and enjoyment of the property has been taken from them for a period that is still on-going.”

He alleged that there was “a lack of required constitutional notice and other notice of actions that affected the property.

“Upon information and belief, the prior owner of the property Greg Briles did not attend the hearing before the Landmarks Commission, never received proper formal notice of any hearing, and there was no publication in any newspaper as required,” Haselhoff averred.

The lawyer also claimed that the defendants, through the Landmarks Commission, both nominated the property for a landmark designation and then so adjudicated it, thus “effectively acting as judge in their own case.”

Trial Court Ruling

On Dec. 15, Los Angeles Superior Court Judge H. Jay Ford III sustained demurrers without leave to amend to all causes of action except slander of title (as to which the parties later reached a settlement). Ford found that Government Code §65009 bars the action.

That section, in subd. (c)(1), specifies that “no action or proceeding shall be maintained” more than 90 days after a city makes a land-use decision.

Ford held that accepting Haselhoff’s position “would contravene the Legislature’s express intent to prohibit challenges to municipal actions beyond 90 days, including a challenge to the landmark decision asserted by Plaintiff.”

Lack of Notice

Ashmann-Gerst found no merit in Haselhoff’s argument that §65009(c)(1), setting a 10-day limit for contesting land-use decisions, presupposes compliance with the requirement in subd. (b)(1) of a properly noticed” hearing. That subdivision says, with enumerated exceptions:

“In an action or proceeding to attack, review, set aside, void, or annul a finding, determination, or decision of a public agency made pursuant to this title at a properly noticed public hearing, the issues raised shall be limited to those raised in the public hearing or in written correspondence delivered to the public agency prior to, or at, the public hearing….”

The jurist responded:

“But subdivision (c) does not refer to subdivision (b) or contain any language regarding a ‘properly noticed’ hearing. If the Legislature had intended to add these conditions to subdivision (c), it could have done so.”

She added:

“Regardless, as the trial court aptly found, section 65009, subdivision (b)(1), is simply a procedural rule that limits a party’s ability to introduce evidence beyond what was raised at the hearing.”

Ashmann-Gerst remarked that “there is no requirement that Briles should have been given notice,” contrary to Haselhoff’s contention, because “[h]e was not the property owner.” Rather, the owner, over the relevant time period, was either a partnership in which Briles was a member or a trust.”

Conflict of Interest

Haselhoff relied on the Jan. 29, 2015 Court of Appeal opinion by Acting Presiding Justice William W. Bedsworth of the Fourth District’s Div. Three in Woody’s Group, Inc. v. City of Newport Beach. In that case, Mike Henn, then a member of the Newport Beach City Council, appealed a decision of the Planning Commission, then, as a Council member, acted on the appeal.

Bedsworth said that one of the “basic principles of fairness” is that “You cannot be a judge in your own case.”

He declared that “bias—either actual or an “unacceptable probability” of it—alone is enough on the part of a municipal decision maker is to show a violation of the due process right to fair procedure,” adding:

“[A]llowing a biased decision maker to participate in the decision is enough to invalidate the decision.”

The wrote that Henn “should not have been part of the body hearing the appeal.”

Ashmann-Gerst’s Response

Ashmann-Gerst said in Tuesday’s opinion:

“Woody’s is readily distinguishable….The Court of Appeal found that the councilmember’s appeal was improper because he did not fall within the scope of persons who were eligible to appeal under the Newport Beach Municipal Code….

“Here, in contrast, the City’s landmarks ordinance specifically allows the Landmarks Commission to nominate a property for designation. And, all we have is Haselhoff’s speculation that the Landmarks Commission’s authority to nominate a property for designation somehow renders the commission automatically and always biased.”

The Grayson House is sometimes referred to as the “House of Rock” because after entrepreneur Elaine Culotti purchased the home in 2010, she and Briles, then her business partner, held parties there featuring rock music.

The case is Haselhoff v. City of Santa Monica, B322168.

Haselhoff was represented by himself and by Michael M. Berger of the Century City firm of Manatt, Phelps & Phillps. Ing for Santa Monica was Deputy City Attorney Benito E. Delfin Jr.

|

|

|

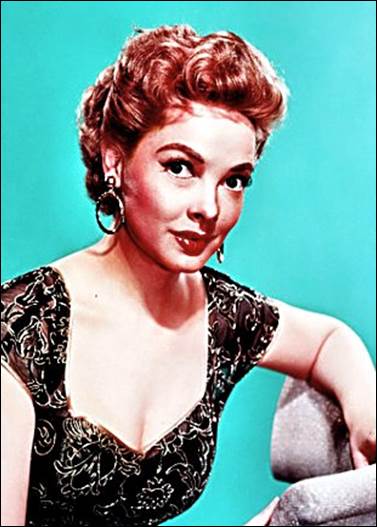

Above is a photograph of singer/actress Kathryn Grayson who owned the home that has been designated a Santa Monica landmark. |

Copyright 2024, Metropolitan News Company