Page 3

C.A. Won’t Void Award Based on Arbitrator’s ‘Corruption’

By a MetNews Staff Writer

|

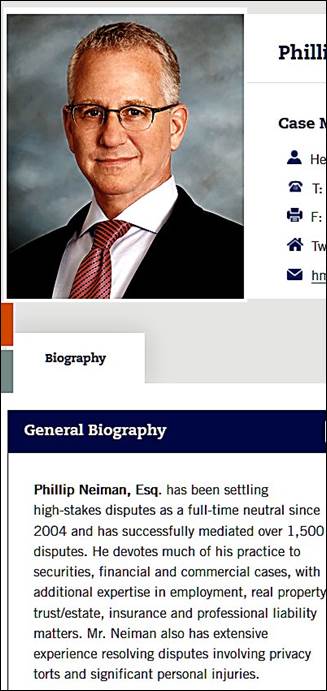

Appearing above is a 2019 screenshot from the JAMS website, captured by the “Wayback Machine,” which stores images that appeared on the Internet. The screenshot shows the representation that Phillip Neiman has been “a full-time neutral since 2004.” Appellants alleged in an appeal, rejected by the First District Court of Appeal on Tuesday, that an award by Neiman in an arbitration should be vacated because Neiman lied about the extent of his experience. |

The First District Court of Appeal has affirmed an order denying a motion to vacate an arbitration award, rejecting the contention that late-discovered evidence shows that the arbitrator’s boast on the JAMS website of 15 years of full-time experience in the field is belied by his 2015 Superior Court complaint against his insurer on a disability policy saying that he began conducting mediations only recently and could only work a few hours a week.

Presiding Justice James M. Humes wrote the unpublished opinion. In it, he commented that the appellant, Seaker & Sons, which claimed “corruption” on the part of the arbitrator, had not even shown that the arbitrator and the plaintiff in the 2015 lawsuit, though bearing the same name, are the same person.

Plaintiff/respondent, App Annie, Inc., in its appellate brief, neither expressly confirmed nor denied that the arbitrator, Phillip L. Neiman, had been the plaintiff in the action filed April 1, 2015 in the Los Angeles Superior Court. In that lawsuit, which was settled later that year, Neiman sued The Northwestern Mutual Life Insurance Company for cutting off his insurance benefits after he divulged his part-time activity as a neutral and its doctors determined he was fit to go back to working for a living.

In the arbitration, Neiman on Jan. 28, 2022, awarded App Annie nearly $8 million in a dispute over the plaintiff’s rescission of its lease for office space in a building near San Francisco’s Union Square which, it turned out, was zoned only for retail uses. Most of the award—$5.46 million—was for the cost of improvements to the premises which, Seaker & Sons contended, were made without the required permits.

Humes said in a footnote:

“App Annie assumes, but does not concede, that the arbitrator and the plaintiff is the same person. Still, it points out that Seaker & Sons presented no evidence proving identicality.”

Not Necessarily Truthful

The presiding justice declared:

“Here, the statements are contained in a complaint wholly unrelated to the subject matter of this litigation. Although we previously took judicial notice of the complaint by separate order, the truthfulness of the complaint’s allegations are not subject to judicial notice.”

He also made note that the complaint was unverified. Humes went on to say:

“We cannot conclude that the trial court was required to accept and credit Seaker & Sons’s proffered evidence or that this evidence established the arbitrator’s corruption. Even assuming the arbitrator and the plaintiff are the same person, the complaint mostly summarizes the time periods when the plaintiff was in contact with his insurance provider and does not read as a complete summary of his entire work history, though it does mention work as an arbitrator. Seaker & Sons asserts that the complaint ‘explains that [the arbitrator] had no business or professional pursuits at all between 2004 and 2011.’ But there is no specific citation to the complaint to support the assertion. Just because the complaint did not describe additional work, it does not prove that the plaintiff performed no such work.”

Same Person

Whether or not Seaker & Sons legally established “identicality,” it appears that the arbitrator and the plaintiff in the 2015 lawsuit are, in actuality, the same person.

The policy was purchased in 1993. The 2015 complaint indicates that “[a]t the time he purchased the Policy, Phil was a practicing attorney.”

The complaint identifies the plaintiff as “Phillip Neiman.” There are two members of the State Bar named Phillip Neiman: the arbitrator, Phillip Louis Neiman, and Phillip William Neiman, who went on inactive status in 2002.

However, the insurance policy, a copy of which is attached to the complaint, lists the insured as “Phillip L. Neiman.”

The complaint sets forth that “Phil eventually had a website made for himself, called Neiman Mediation.” Phillip Louis Neiman operated such a business before joining JAMS in 2018 (leaving it in 2022).

Neiman’s Complaint

Neiman said in his 2015 complaint that the insurer was in error in estimating his capacity to resume working, maintaining:

“…Northwestern had no reason to believe that Phil could work 60 hours a week, or even 10 hours a day. Phil struggles to work 10 hours a week. He can only work a maximum of three hours a day, and only on nonconsecutive days.”

The pleading adds:

“Northwestern’s termination of benefits has caused Phil to suffer significant financial harm. He has no savings, and is unable to hold fulltime, or even regular part-time employment due to his illness.”

It relates that, impliedly in or after 2011, he “chose to volunteer with mediation services at a local court,” doing so, “only to improve his depression and anxiety.”

Appellant’s Brief

Seaker & Sons argued in its opening brief:

“The arbitrator in this case, Phillip Neiman, demonstrated acute dishonesty that renders him unfit to adjudicate anything. In his efforts to attract business, Neiman misled prospective litigants about both his honesty and his professional experience. By doing so, Neiman deprived litigants of the right to informed consent that is integral both to the choice of arbitration as a means of dispute resolution and to the arbitration process itself.

“On the website biography to which his arbitration organization, JAMS, directed parties considering whether to accept Neiman as an arbitrator, Neiman told prospective arbitration clients that he had been a full-time arbitrator since 2004, with ten years’ experience atop an investment bank before that.

“What Neiman didn’t tell his prospective clients was that this self-promotion was a lie. In sharp contrast to what he told potential customers in marketing his services as an arbitrator, Neiman set out his actual professional history in a superior court complaint he filed against his disability insurer….As of March 31, 2015, the 2015 Complaint averred, Neiman had been totally disabled by severe depression since 2004, and had relied on strong psychotropic medication since then. Neiman collected disability payments of nearly $1 million during this period.”

The brief says that when Neiman joined JAMS in 2018, “Neiman and JAMS told the world” in an announcement, “that Neiman had been a full-time arbitrator and mediator since 2004…, seven years before he conducted his first mediation, and at least eleven years before he could work even ten hours per week.”

The appellant asserted:

“In short, Seaker was prejudiced by Neiman’s misconduct, which put Seaker at the mercy of an inexperienced, dishonest arbitrator. Seaker is entitled to a new and different arbitration before an honest arbitrator who actually has the qualifications that he advertises.”

App Annie’s View

App Annie (now known as “Data.ai Inc.”) said in its brief:

“A finding in this case that the Arbitrator was required to disclose an alleged struggle with depression that occurred years before the arbitration or expressly qualify his representation of himself as a ‘full time’ neutral due to such alleged past struggles, would subject many neutrals and judges to great uncertainty in the disclosure process and would constitute an invasion of privacy not supported by the law.”

Neiman, admitted to the State Bar in 1990, left his practice in 1994 to become an investment counselor. App Annie’s brief says:

“There are no direct allegations in the unverified complaint that state that the Arbitrator was not a full time neutral since 2004….Instead, Seaker attempts to argue that the Arbitrator’s biography contained misrepresentations based on unfavorable inferences Seaker draws from the allegations. For example, Seaker argues that because the Arbitrator filed a claim for ‘total disability’ in 2004, it cannot be that he also began working as a neutral that same year….But ‘Total Disability’ was a defined term in the insurance policy at issue meaning ‘unable to perform the principal duties of his occupation’ ‘at the time he becomes disabled’ which at that time was that of an investment banker….The allegations make clear that the focus was on the Arbitrator’s ‘inability to perform the material duties of his investment banking career.’…The fact that he could no longer perform the duties of an investment banker does not mean that he lied when he said that he began work as a neutral in 2004.”

No Direct Disputation

The brief, while contending that Seaker & Sons failed to demonstrate that Neiman had not worked as a neutral since 2004, does not contain an effort to show that he had, in fact, done so.

It points out:

“Here, Seaker could have investigated the personal and work background of the Arbitrator if it was concerned about any of these issues prior to accepting the Arbitrator for this case. The materials Seaker now relies on, including the unverified 2015 complaint, were all just as available prior to the arbitration as they were after the arbitration.”

Filed in Los Angeles, the case was transferred to San Francisco. Humes’s opinion affirms a judgment by San Francisco Superior Court Judge Charles Haines.

The case is App Annie, Inc. v. Seaker & Sons, A165384.

Copyright 2023, Metropolitan News Company