Wednesday, February 10, 2010

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

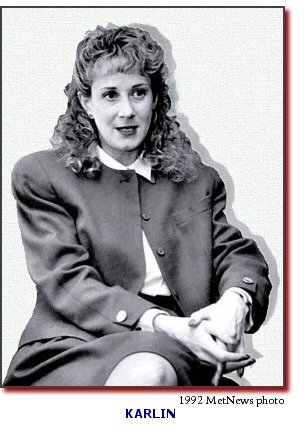

Reiner Mounts Assault on Judge Joyce Karlin Over Sentencing of Grocer Soon Ja Du

By ROGER M. GRACE

118th in a Series

IRA K. REINER did it again.

When then-Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Joyce Karlin (since retired from the bench) came under attack in the African-American community in 1991 for placing on probation a Korean-American shopkeeper convicted of voluntary manslaughter of a 15-year black girl suspected of shoplifting, Reiner instituted a blanket affidavit policy against the judge and challenged the sentence via a writ proceeding.

Reiner failed to put Karlin’s sentencing decision in perspective. As he had in the past, often, he sought to advance his own political career through denigration of some other office-holder, posing as the public’s protector.

His actions in this instance were reminiscent of his assault on a Los Angeles Superior Court commissioner, Daniel Calabro (since retired), when he sought to draw political support from the African-American community by exposing the jurist as a racist…which he wasn’t. Reiner took a remark out of context, a fact that was generally grasped.

![]()

In reporting Karlin’s 1997 decision to leave the bench, a City News Service report ably summarizes the case which had roused emotions six years earlier involving shopkeeper Soon Ja Du and the slain girl, Latasha Harlins:

The killing of the l5-year-old Harlins, a ninth-grader at Westchester High School, came within two weeks after the Rodney King beating and underscored tensions between the Korean and black communities.

Many Korean-Americans run mom-and-pop markets in black communities, and some African-Americans have wondered why they are unable to get loans for such enterprises when foreign-born merchants can.

But many Koreans take out loans from members of their community, not banks, to gain a foothold in the business world.

Other tensions between the two groups are traced to language barriers and cultural misunderstandings. Spike Lee’s “Do the Right Thing” spotlighted a similar fictional situation in New York City’s Bedford Stuyvesant area.

Du, who reportedly had begged her family to get out of the grocery business because of her fear of being robbed, supposedly had been told that gang members dress in all black.

Harlins, who was in dark clothing, came into the Empire Liquor market, went to get a bottle of orange juice worth $1.79 and put it into her backpack.

Du, then 51, confronted her about it and an argument ensued, which led to punches being thrown. Harlins supposedly threatened to kill Du, who got a .38 caliber handgun from beneath the counter, unaware that it had been rigged by another employee to fire quickly in the event of a robbery.

As the teenager turned to leave the store, the gun discharged. The bullet struck Harlins in the head, killing her, and the shooting was captured on the store’s surveillance tape and widely shown by the media.

![]()

Du was convicted by a jury on Oct. 11, 1991, in

connection with the fatal shooting the previous March 16. Karlin sentenced her

on Nov. 15 to 10 years in state prison, but suspended the sentence and placed

her on five years of probation, on  condition that she pay

$500 to the restitution fund, reimburse the girl’s family for medical and

funeral expenses, and perform 400 hours of community service.

condition that she pay

$500 to the restitution fund, reimburse the girl’s family for medical and

funeral expenses, and perform 400 hours of community service.

The Nov. 19 issue of the San Diego Tribune relays this report from Los Angeles:

“District Attorney Ira Reiner ordered prosecutors yesterday to boycott the judge whose light sentence for a Korean-born grocer convicted of killing a black teen-ager sparked outrage.

“ ‘This was such a stunning miscarriage of justice that Judge (Joyce) Karlin cannot continue to hear criminal cases with any public credibility whatsoever,’ Reiner said.

“The district attorney, who is facing a tough re-election battle and has become increasingly vocal on a number of major issues in recent weeks, said the action against Karlin was ‘unusual, but not rare.’ ”

A Nov. 20 Los Angeles Times editorial remarks:

“The decision by a local judge to sentence a South-Central Los Angeles grocer to probation—rather than prison—for killing a black teen-ager was questionable, no doubt about it. But Los Angeles Dist. Atty. Ira Reiner is only bringing more heat to an already overheated murder case by joining in the criticism so vociferously….

“African-American leaders have called for the community anger generated by Karlin’s ruling to be channeled constructively. Even Karlin expressed a hope that leniency might promote a healing process. But healing won’t be helped along by Reiner’s outburst.

“Reiner called Du’s sentence ‘a stunning miscarriage of justice’ and swore to keep Karlin—a former prosecutor made a judge only a few months ago—from ever trying another criminal case. That is technically possible under a California law that allows attorneys to remove one judge from a case—without an explanation. Reiner said he will order his staff to invoke that privilege every time Karlin is assigned to a criminal case. It’s perfectly legal—but is it wise? Should a jurist be blackballed for one controversial decision?

“Reiner is up for reelection next year. The Harlins case has been so painful and sensitive that one is left with the uncomfortable suspicion of a politician trying to use a community’s collective grief for his own ends.”

Shortly after instituting the blanket affidavit policy, Reiner lifted it, agreeing to disqualify Karlin only on a case-by-case basis.

![]()

It was at a press conference that Reiner announced his decision to seek a writ overturning the sentence. The Nov. 27 issue of the MetNews reports:

Reiner acknowledged…yesterday that a successful challenge of the Karlin’s sentence in the case would be “a longshot.” But, he added, “it’s essential that an appeal be taken” because “the sentence was clearly illegal—a judge cannot use a sentence as an indirect way to reduce a verdict.”

Reiner explained:

“The jury found the defendant guilty of voluntary manslaughter. That means the jury found the defendant intended to kill this girl. The judge [in explaining her sentence] said she had serious questions about whether the defendant intended to kill the girl.

“Well, the jury had already determined that fact.

“Apparently the judge did not agree.

“[Karlin] could have [ordered] a new trial, or reduced the charge to involuntary manslaughter. Instead, she [issued a] sentence that had the practical effect of nullifying the jury verdict.”

In explaining her sentence, Karlin noted that the .38 revolver Du used to shoot Harlins had been stolen from the family and returned with a hairpin trigger that, she said, in effect made the gun “an automatic weapon.” The trigger formerly on the gun could not go off accidentally, Karlin said, and “a woman of Mrs. Du’s size would have to decide consciously to pull the trigger and to exert considerable strength to do so.”

She added:

“But that was not true of the gun used to shoot Latasha Harlins. I have serious questions in my mind whether this crime would have been committed at all but for a defective gun.”

A Dec. 4 news article in the Sentinel, a newspaper aimed at the the African-American community, says of Reiner’s decision to challenge the sentence:

“Although Reiner’s announcement to appeal gladdened many hearts in the African-American community, it should be noted that a prosecution appeal of a case is rare and usually unsuccessful because of the weight given to judges.

“Charles Lloyd, the Black attorney who defended Soon Ja Du, said that he was not bothered by Reiner’s decision to appeal.

“ ‘He can appeal, but he won’t be successful....He’s just playing politics, and the people are being misled. He’s throwing kerosene on this thing. He’s pandering to the public, and I think it’s terrible,’ said Lloyd, who believes the announcement is politically motivated as Reiner is gearing up for re-election.”

![]()

The MetNews endorsed Karlin on Dec. 23, before any challenger had declared candidacy, setting forth in its editorial:

“Inherent in our endorsement of Karlin is the dismissal of the candidacy of any person who might challenge her, without regard to the qualifications of that yet-to-emerge soul. Ordinarily, this would be precipititous. But here, any candidacy would be grounded on opposition to one particular sentence—a slim basis for a challenge under any circumstances, and certainly no basis for a challenge where the judge strove to fulfill her obligations, acting out of regard for ethics, not politics.

“We believe that it is not too early to speak out in favor of the candidacy of Judge Joyce Karlin, and against the lynch-mob furor that will in all probability propel someone into challenging her at the polls.”

The editorial alludes to Reiner’s stance by saying:

“While the presiding judge of the Superior Court, Ricardo Torres, has in numerous instances this past year displayed what we regard as abominably bad judgment, we applaud his forthright and prompt defense of Karlin, when she came under attack by the district attorney.”

![]()

Reiner’s office on Jan. 10, 1992, filed a 100-page writ petition in the Court of Appeal for this district. On Feb. 10, Div. Five, in an order by Acting Presiding Justice Herbert Ashby, issued an order to show cause why a writ should not be granted. A Feb. 12 MetNews editorial expresses this reaction:

In a climate of outrage by members of the black community over the leniency shown Du, the publicityseeking, vote-coveting demagogue who’s up for election as district attorney is seeking a writ overturning the sentence. In saying that Du didn’t mean to fire the gun, he proclaims, Karlin contradicted the jury, and in so doing, based her sentence on an impermissible factor.

Even so, a reading of the entire discourse at the time of sentencing reveals with certainty that Karlin was of such mind that she would have imposed the same sentence had she not taken this factor into account. She was persuaded that Du was not a danger to society, and did not require rehabilitation or incapacitation. While use of a gun ordinarily requires incarceration, she found three factors rendering the case an “unusual one”: the gun was possessed for self-protection, not criminal aggression; the defendant had no criminal record; there were “circumstances of great provocation, coercion, and duress.”

Indeed, Karlin did not simply put out of mind the jury’s determination, and substitute her own judgment—for “provocation, coercion, and duress” would have no bearing if this were a case of involuntary manslaughter. These would be relevant factors only in explaining an intentional killing.

Also, Karlin found that the victim, Latasha Harlins, was not especially vulnerable, having used her fists as weapons “just seconds before the shooting.” This comment tends to show the judge was not acting under the misimpression that this was simply an accidental shooting.

Karlin found that Du overreacted, but that her over-reaction was “understandable” in light of the climate of intense fear engendered by “robberies and terrorism” in the store. This, too, assumes a volitional act, not merely a mishap.

Taken in context, it is clear that Karlin’s reference to the possibility that the shooting was accidental was more of an aside than a pivotal determination. It is unmistakable that in the absence of that consideration, she would have come to the same sentencing conclusion.

A writ petition that ordinarily would have met with a postcard denial has, instead, induced an order to show cause. This comes at a time when Karlin is facing a possible recall based on the sentence, and the presiding judge of the court, Ricardo Torres, is likewise targeted just because he wouldn’t shift Karlin from a criminal department at the Compton courthouse at the snap of fingers.

Acting Presiding Justice Herbert Ashby and his cohorts have deferred to the noise-makers. In so doing, they have more severely threatened judicial independence than any judge-bashers on the outside, for they have given credence to the cause of those who would bully trial judges into making politically expeditious decisions, rather than exercising discretion as their consciences dictate.

It is true that the appeals court has not mandated that Karlin vacate the sentence. She has the option of not doing so, and having the county counsel argue the validity of her action. This nonetheless constitutes a tentative determination that she erred—thus lending respectability to District Attorney Ira Reiner’s politically motivated stunt in seeking the writ.

Karlin did not alter the sentence. The Court of Appeal on April 21, 1992, issued a decision denying a writ, concluding that the sentence fell within the guidelines. Reiner sought review by the California Supreme Court, which was denied July 16, 1992.

Karlin’s campaign was guided by political consultant Joe Cerrell, and she prevailed in the 1992 primary over three challengers. She now uses—though she didn’t then—the surname of her husband, William Fahey, who is now…and wasn’t then…a judge of the Los Angeles Superior Court. Joyce Karlin Fahey, who recently served two terms as mayor of Manhattan Beach, is now a mediator.

Copyright 2010, Metropolitan News Company