Monday, December 21, 2009

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

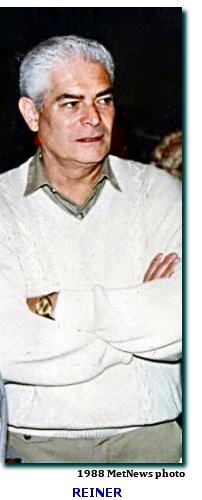

Reiner Turns DA’s Investigators Into ‘Lackeys,’ Performing Personal Chores

By ROGER M. GRACE

112th in a Series

IRA K. REINER was, at least so far as is generally known,

never officially investigated in connection with the possible commission of a

crime. However, in 1987, one lawyer publicly suggested that a look be taken at

whether the DA had committed  a prosecutable misuse of public funds; a 1988

examination by a major newspaper pointed to his uses of public resources for

seemingly personal purposes, and an editorial followed calling for a county

audit; and a rival candidate for district attorney in 1988 urged criminal and

civil probes by state and local authorities into Reiner’s spending.

a prosecutable misuse of public funds; a 1988

examination by a major newspaper pointed to his uses of public resources for

seemingly personal purposes, and an editorial followed calling for a county

audit; and a rival candidate for district attorney in 1988 urged criminal and

civil probes by state and local authorities into Reiner’s spending.

The controversy was triggered by an event on June 15, 1987. Reiner was having dinner with his wife, Diane Wayne (a member at that time of the Los Angeles Superior Court), and their two children—Annie, 11 and Tommy, 8—at Spago, then located in Hollywood on the Sunset Strip. Outside, three men, at gunpoint, kidnapped Reiner’s bodyguard/driver, Henry Grayson, and drove off in the county-owned 1986 Buick Park Avenue assigned to the DA.

As attorney Thomas Hunter Russell of Hollywood saw it, the theft of the car was the second “rip off” of taxpayers that day. His letter-to-the-editor, published by the Los Angeles Times on July 5, asserts that the first rip-off was on the part of Reiner who used a county car, and a county employee to drive it, not for “official business” but for personal purposes. The letter says:

“Who will prosecute D.A. Reiner for the manifest abuse of the public trust and the misuse of county property and funds involved in using an expensive county car and a highly paid civil servant to haul the Reiner family around to children’s birthday parties, etc.[?] I understand that this was not an isolated incident and that this car and driver (whose salary and benefits cost the county more than $100,000 last year) are frequently seen outside restaurants frequented by the Reiner family.

“Having been disciplined recently by the State Bar for his unethical conduct while city attorney, can we trust this glitzy politician to have himself investigated and prosecuted? I think not.

“It is time that the Board of Supervisors, the grand jury, and/or the attorney general investigate the misuse of county funds, personnel and property by Reiner.”

The Times’ lawyers probably blanched when they saw that a letter had been published not only accusing Reiner of criminality on that one night, but criminality on an ongoing basis, with the allegation of frequency predicated on hearsay from an unidentified source.

It turned out, however, that Russell’s information was apparently accurate.

![]()

Whether prompted by his letter or not, an investigation was launched. It wasn’t undertaken by a government agency, which is what the lawyer had in mind, but by a newspaper—the Herald Examiner.

In the immediate aftermath of the abduction of Reiner’s bodyguard and theft of the auto, the possibility loomed that the incident was a precursor to acts aimed directly at Reiner or his family. It would hardly have shocked anyone to see in an Associated Press story four days after the incident that Reiner and his family “are getting special protection.”

But momentary security consciousness apparently turned into a continuing security operation rivaling those conferred on heads of state, with investigators, according to a Herald Examiner probe, performing personal chores for the Reiner family.

A March 31, 1988 article by Nancy Hill-Holtzman quotes “one high-ranking investigator” as saying that investigators were used by Reiner in such a way that they had become “just plain lackeys for him.”

Hill-Holtzman (later a reporter for the Times) gives these examples:

►An employee of Hollyway Cleaners confirmed that a man fitting the description of Reiner’s main driver/bodyguard Grayson often picks up his boss’ laundry before work in the morning. A source told the Herald Examiner that another driver also has picked up the laundry. Another source said Grayson also has picked up the children, babysitters and maid on county time.

►According to several sources, a county car driven by an investigator, who earns up to $35 an hour if working overtime, is dispatched at least two hours early to save Reiner a good parking place at professional football games. Reiner arrives later with a second bodyguard.

Both investigators are on duty during the game, with one of their assignments being to take Reiner’s son, Tommy, 10, to the bathroom the bureau sources said.

►A trip to a Bruce Springsteen concert at the Coliseum in September 1985 entailed at least three cars and several agents who arrived hours early to check entrance and exit routes for Reiner and a group of his friends, one participant said.

►When Reiner vacationed in Europe in 1986, his empty house was guarded round-the-clock for weeks at a time, according to several bureau sources, some of whom were directly involved.

With the bare minimum of four senior investigators, split into two teams working 12-hour shifts, the bill for two weeks would be $15,862. The figures are computed by the Herald Examiner using a 1987 bureau salary schedule for senior investigators.

The article goes on to say:

[A] way Reiner has changed procedures is by expanding the definition of a security alert, during which protection is increased in response to a threat or fear of one, sources said. Reiner has decreed that a threat to him warrants complete protection for his wife and children.

On those occasions, teams of investigators follow his children’s school bus, then wait outside school all day to follow it home, investigators said.

A separate team of investigators picks up Reiner’s wife and drives her to work. They sit in the back of Wayne’s courtroom, despite the presence of the bailiff who is responsible for her safety, and has access to reinforcements when needed, the sources said.

….At least 10 investigators are used per 24-hour period and they are kept in place about four times as long as in past administrations, sources in the bureau said.

In a companion article, Hill-Holtzman reports that special alerts went into effect on such occasions as when Reiner in 1986 dropped charges against five defendants in the McMartin Pre-School child molestation case and when he appeared later that year on CBS’s “60 Minutes” and berated the case (though charges remained against two defendants). These events would not seem to have been apt to spark physical assaults on Reiner or his clan.

![]()

An April 1, 1988 editorial in the Herald Examiner comments:

We can’t pretend to second-guess, how much increased security can be justified on the basis of Reiner’s increased visibility, high-profile criminal cases, the fact that his wife is a Superior Court judge or for some after-hours events related to official county business. The DA is no doubt right in saying that ‘Security is not a perk, it’s an intrusion on your life.’

But it should not be a personal chauffeur and valet service for the entire Reiner family as well, especially when county taxpayers are expected to pick up the tab.

In 1977, Reiner rode into prominence as the tightfisted L.A. city controller who called local officials to account for their junketeering at public expense. He could polish his tarnished image today by asking the county auditor-controller’s office to examine his security budget for ways to save money, and by releasing the results of that report.

Let’s see if the old fiscal watchdog’s still got his bite.”

A Times article, also published on April 1, reports:

Deputy Dist. Atty. Lea Purwin D’Agostino called Thursday for a county audit of the estimated $400,000 spent on personal security for Ira Reiner during the first three years of his tenure as district attorney.

D’Agostino, who is on vacation from her job while campaigning to unseat Reiner in the June 7 election, called the expenditure a “flagrant abuse and misuse of . . . taxpayers’ funds for Reiner’s personal benefit.”

In a letter to county Auditor-Controller Mark H. Bloodgood, D’Agostino demanded a “full and complete” accounting of the money spent on personal security for Reiner and his family.

She also called for a “complete criminal and civil investigation” by the state attorney general, an investigation by the State Bar and “full reimbursement” by Reiner for “funds he has used for his own personal expenses.”

The accusations were leveled at Reiner after a report in the Los Angeles Herald Examiner revealed that the cost of protecting Reiner was 50% to more than 100% greater than that spent on his two most recent predecessors—Robert Philibosian and John Van de Kamp—and generally higher than that expended on district attorneys in other large U.S. cities.

![]()

Had Grayson been inside Spago while the Reiner family was there to celebrate Annie’s graduation from elementary school, none would doubt that his role would have been that of bodyguard. The question then would have been whether a DA is so high-profile a figure as to need protection while dining in a restaurant, as opposed to being present at crowded public events such as like football games or concerts. But Grayson was outside the restaurant. Unmistakably, his role was that of a chaueffer, waiting idly for his passenger or passengers to reemerge.

Once Reiner was in the car, being driven, Grayson was a protector. Is a DA so likely a target as to require an armed escort at the wheel while coming home from dinner? Mayor Tom Bradley, for one, managed to drive himself to and from work, in a car with bullet-proof glass, without incident.

Housewatching for two weeks? The argument for that seems thin.

Fetching clothes from Hollyway Cleaners? That appears to be a clear abuse…though Reiner’s side of it was that on occasions when he went into a market, Grayson might have popped into the cleaning shop next door—now and then—or maybe they switched roles. If Reiner was so desparately in need of protection, why didn’t he need Grayson right by his side in the market or cleaners?

![]()

The Herald-Examiner articles make no mention of the possibility which Russell and D’Agostino raised that Reiner might be breaking the law.

Penal Code §424 provided then, as it does now:

“Each officer of this state, or of any county...charged with the receipt, safekeeping, transfer, or disbursement of public moneys, who...[w]ithout authority of law, appropriates the same, or any portion thereof, to his own use, or to the use of another...[i]s punishable by imprisonment in the state prison for two, three, or four years, and is disqualified from holding any office in this state.”

Clearly, the DA did not pocket public moneys. Nonetheless, Reiner did cause public moneys to be expended in the form of payment to Grayson of a salary while performing tasks for him.

Assuming these tasks did not constitute necessary bodyguard functions, and served Reiner’s personal purposes, only, a basis existed for investigating possible violations of §424.

The scope of §424 was delineated in People v. Sperl, decided by this district’s Court of Appeal on Jan. 21, 1976. The court upheld convictions of former Los Angeles Marshal Timothy Sperl whose misdeeds included assigning a deputy marshal to chauffer James Hayes, then a member of the state Assembly (later a county supervisor).

The opinion recites that Sperl contended that “he did not misappropriate ‘public moneys’ within the meaning of Penal Code section 424..., since his conviction was based upon the ‘use of a county car and the services of a driver on county time,’ and services do not constitute public moneys.” The response in the opinion is that “[t]his contention is without merit” because evidence showed that “the cost to the county for [the driver’s] services and the operation of the county vehicle while transporting Hayes, his family and staff, amounted to $1,956.23.”

The county was, of course, under no duty to provide transportation services to Hayes (whose support Sperl wanted in opposition to merging the Marshal’s Office into the Sheriff’s Office), while a clear duty did exist to provide security to Reiner as DA, which in some instances involved transportation. The question is whether services that were provided exceeded those which the county had a duty to provide.

By the way, Government Code §8314, which bars prosecutions under §424 for “incidental and minimal use of public resources by an elected…local officer,” was not yet in effect. And if it had been, would it have applied?

The answer to that doesn’t really matter. Answers to the various questions raised in 1987 and 1988 that were of consequence were never addressed by any official body.

Copyright 2009, Metropolitan News Company