Tuesday, October 28, 2008

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

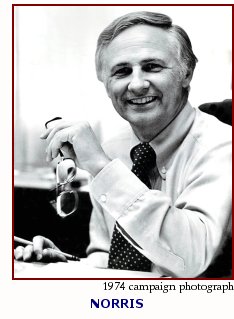

Younger Draws Smears, Including Allegations of Criminality, in 1974 AG Race

By ROGER M. GRACE

Seventy-Seventh in a Series

EVELLE J. YOUNGER in 1974 drew no competitor for the Republican nomination for attorney general, the post he then held. His opponent in the general election was William A. Norris who, like Charles O’Brien four years earlier, carried on a smear campaign, alleging that Younger had committed egregious misdeeds as Los Angeles County district attorney.

An Oct. 22 article in the Times says that “[i]n an election year supposedly tailormade for Democrats” in light of the popular backlash against Watergate, Norris “is badly trailing in the polls and having trouble denting Younger’s incumbent armor.” The analysis continues:

“For that reason, the peppery Democrat daily is on the attack and has turned the campaign for attorney general into one of the bitterest and most controversial statewide races now in progress.”

Norris sought to make a major issue out of Younger’s involvement with Geotek, a fraudulent oil-drilling venture in which Younger, himself, had made a $16,500 investment…though the funds he paid were derived from a loan from Geotek’s president.

As a Sept. 10 City News Service story by then-reporter Dana Rohrabacher (now in his ninth term in the U.S. House of Representatives) tells it:

“Norris charged that Younger shoved aside complaints he received [as district attorney] about Geotek because of his friendship and business relationship with the corporation’s chief executive officer, Jack Burke.

“ ‘Younger turned a blind eye and a deaf ear for years to Burke’s maneuvers because Younger—himself an investor in Geotek—was part of the action and had no desire to upset the Geotek bandwagon,’ Norris claimed.

“Younger has denied that the complaints ever reached him.”

The Sacramento Bee and the other pro-Democrat McClatchy newspapers were backing Norris. A Page One Bee article on Oct. 7 says:

“While he was district attorney of Los Angeles County, Atty. Gen. Evelle J. Younger ignored a complaint that oil drilling investment programs in which he has a personal stake were fraudulent, according to an affidavit on file in federal court.

“This contradicts Younger’s repeated contention that he never received any complaints about the programs.

“The affidavit was given to federal securities investigators by an investor in the oil drilling venture, Bernard Kamen, a 60-year-old retired manufacturers’ representative from Sepulveda in the San Fernando Valley.”

![]()

Younger had provided a written statement to the Securities Exchange Commission in 1972 about the Goetek case. At a press conference in Los Angeles on Oct. 9, Norris made much of Kamen’s affidavit. He told reporters,according to the Associated Press’ account, that “if the facts establish—as they appear to do—that Younger lied to the Securities and Exchange Commission…that’s a felony under federal law.”

He did say “if.”

Norris declared, the AP dispatch says, that Kamen’s affidavit was “new evidence—very powerful evidence under oath—indicating that Mr. Younger lied.”

I did not know that an affidavit is “very powerful evidence.”

At the press conference, Norris stopped short, barely short, of ac cusing Younger of having committed a felony.

cusing Younger of having committed a felony.

However, a United Press International dispatch from Sacramento indicates that Norris, that same day, released a statement in which he did allege criminality on the part of state attorney general. The dispatch begins:

“William A. Norris, Democratic candidate for attorney general, demanded Wednesday that his Republican opponent testify to a federal grand jury about an alleged $30 million oil drilling fraud in which he owned a portion.

“Norris said in a statement that incumbent Atty. Gen. Evelle J. Younger ‘violated the federal statute making it a felony to falsify or cover up any material fact in cases under investigation by a federal agency.’ ”

The federal grand jury had already indicted Burke and two associates. Their scheme purportedly entailed selling stock, to about 2,000 investors, in a company that was to drill for oil at sites which the defendants knew were dry. Obviously, Younger was not about to dignify Norris’ charges by instigating testimony by himself before a grand jury (or, as Norris later demanded, taking a polygraph test).

But what if Younger had wanted to take Norris up on the dare? How does one go about arranging to testify before a grand jury that has already handed up its indictment in a case?

More significantly, what can be said of the fitness of a candidate for attorney general—the state’s chief prosecutor—who would publicly allege the commission of a felony based on an affidavit unsupported by corrobating evidence?

![]()

Younger provided a detailed response to the Bee. It appears in full in the newspaper’s Oct. 11 edition.

In it, Younger brands as “absolutely untrue” the

allegation that as district  attorney, he failed to investigate complaints concerning

Geotek. He declares to be “accurate and true” this statement by him of Aug. 16,

1972, to the SEC:

attorney, he failed to investigate complaints concerning

Geotek. He declares to be “accurate and true” this statement by him of Aug. 16,

1972, to the SEC:

“To the best of my knowledge, I did not receive any complaints or requests for action concerning Mr. Burke or his activities when I was District Attorney of Los Angeles County. I have checked with Deputy District Attorney Bernard Gross, head of the Los Angeles County District Attorney’s Major Fraud Section, and have been advised that there is no record in that office to this date of any complaint ever having been filed concerning Mr. Burke. I do remember on one occasion talking to a man I know only by sight in the locker room at the Los Angeles Athletic Club. He identified himself as a fellow investor who was pessimistic about the prospects of the enterprise as an investment. I don’t recall any telephone calls to this effect. I am certain, however, that no one made any allegations to me of any violation of any law by Mr. Burke or his associates.”

Younger’s response continues:

Mr. Kamen, who is quoted in The Bee, is wrong. After our office learned his name and the month he alleges he called me, my secretary Mrs. Lily Ring, examined her daily logs and [she] reports (see attached) that notations in the book show that a Mr. Kamen phoned my office on June 13, 1969; that I did not talk to him; and that his phone call was referred to then Chief Deputy District Attorney, now Superior Court Judge, William Ritzi.

Mrs. Ring’s notation does not prove conclusively that Mr. Kamen spoke to Judge Ritzi. However, it clearly indicates that I did not speak to Mr. Kamen. Also, the pertinent question is not whether I received a phone call but what (if I did) the caller said. If a stranger got by my secretary—which is unlikely—and talked to me about the weather, alimony payments, or the stock market—matters over which I had no official concern, I might have forgotten the call; and Judge Ritzi probably would have forgotten such a call. However, I am and always have been absolutely certain that neither Kamen nor anyone else phoned me when I was District Attorney and accused Jack Burke of any criminal activity.

In this connection you refer to a longhand letter Kamen presumably wrote to a friend in June of 1969. In this letter he describes a phone conversation which he claims to have had with me but he says absolutely nothing to indicate that he had accused Burke of any illegal activity. It’s only when he prepared an affidavit over two years later that he claims to have told me over the phone that “there was fraud involved” in Burke’s operation.

Most of all this entire episode demonstrates your newspapers’ obvious unfairness in accepting a totally unsupported allegation. Mr. Kamen is confused, or his memory is faulty.

If he had any evidence of criminal conduct and failed to make a proper written complaint, he did a disservice to me and thousands of other investors.

Also he claims he and his friends had already sent complaints in writing to the Corporations Commissioner. Isn’t it strange that he would not have sent the District Attorney copies of these letters or written to the District Attorney if in fact he thought a criminal investigation should be undertaken?

![]()

How did Norris respond? He did not withdraw his allegation. Rather, he set about trying to prove it, staging a press conference on Oct. 14 in Los Angeles. He presented as a witness none other than Kamen’s accountant who declared that Kamen told him that he had talked to Younger by phone about Geotek and wasn’t happy about the response he got. (This was, of course, hearsay, but hearsay is fully admissible at press conferences, though entitled to little if any weight in the court of public opinion.)

Kamen’s secretary was also scheduled to appear but didn’t show up. She was supposed to tell reporters that she had placed the call from Kamen to Younger. A Times staff writer telephoned her at work and, as his story the next morning recounts, she said she wasn’t sure if she placed such a call or not.

Kamen was not there to be questioned. He was said to be vacationing in Mexico. If he had been credible, it might be assumed that Norris, with all that was at stake, would have chartered a plane to bring him to the Greater Los Angeles Press Club for the news conference.

Maybe Kamen thought he was talking with Younger when he chatted with Ritzi. Maybe he lied about talking to Younger to impress his accountant. It’s impossible to get by the “maybes.” Norris did not present his supposed percipient witness.

Could it also be supposed that maybe Kamen told the truth in his affidavit, and Younger lied? Theoretically, that’s possible, but under all circumstances—including Younger’s background and reputation for integrity, the lack of any meaningful substantiation of the charge, and Kamen’s apparent unwillingness to talk with reporters, it seems awfully far-fetched.

The U.S. attorney for the northern district of California, James L. Browning Jr., to whom Norris made a complaint, concluded that Younger “committed no improprieties” in connection with the Geotek matter. As the Bee was quick to point out, Browning was a Republican. Browning, who went on to successfully prosecute heiress Patty Hearst in 1976 on a bank robbery charge, later served as a judge in San Mateo County, appointed first to the Municipal Court, then the Superior Court, by Republican Gov. George Deukmejian.

![]()

An Associated Press campaign wrap-up carried by newspapers the Saturday before the Nov. 5 election saves for the final paragraph a statement by Norris that can only be interpreted as an allegation that Younger took a bribe from Burke. It says:

“Younger’s Democratic rival hammered away on Younger’s role in the GeoTek scandal and said a $16,500 loan to Younger by GeoTek president Jack Burke ‘was actually a payoff for services rendered.’ ”

What “services” could be inferred other than not investigating or prosecuting?

The utterance of that charge, and Norris’ other charges of felonious misconduct on the part of Younger—charges unsubstantiated by evidence—reveal that the Democratic Party in 1974 put forth as its nominee for attorney general a candidate who, like its nominee of four years earlier, was uncommitted to truth or fair play. This was in contrast to its successful nominees in years of the recent past: Stanley Mosk (later a state Supreme Court justice), Pat Brown (later governor) and Thomas Lynch.

President Jimmy Carter nominated Norris to the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals on Feb. 27, 1980; he was confirmed by the Senate on June 18 of that year; Norris assumed senior status in 1994; he retired three years later. Carter is, like Norris, a Democrat.

The differences between the appointment of the Republican Browning to judgeships by the Republican Deukmejian and the selection of the Democrat Norris by the Democrat Carter are significant. Browning had a solid background in law, while Norris didn’t; Norris had hurled scurrilous charges at Younger in the 1974 campaign while Browning, in the course of his career, had not evinced any such irresponsibility.

The March 29, 1976, issue of Time Magazine quotes Browning as saying, with respect to the Hearst prosecution:

“I was told by some people that if what I wanted was a federal judgeship I shouldn’t try the case. But I never felt that I could turn over the handling of the trial to any of my deputies.”

Something is wrong with this picture. A U.S. attorney must settle for a state trial-court judgeship in San Mateo County; a lawyer who has amply demonstrated a propensity for hurling wild charges is rewarded by his party not merely with a judgeship, but a federal judgeship, and, despite the lack of any judicial experience, on the appellate level.

Luck, it would seem, has as much, sometimes a great deal more, to do with success than ability. Younger serves as an example of that. Men with far less competence than he became governor; he didn’t.

Copyright 2008, Metropolitan News Company