Wednesday, June 15, 2005

Page 7

PERSPECTIVES (Column)

Harry T. Shafer: Seeker of Justice, Teller of Jokes

By ROGER M. GRACE

Harry T. Shafer, who died Saturday, was a judge imbued with a sense of humor and a love of humanity.

He was principled and gutsy, a liberal yet a skilled businessman, a maverick.

On a bookshelf behind the desk in his chambers when he was on the Los Angeles Superior Court you would find “Multi-state Aspects of Domestic Relations Cases” right next to a book of party jokes. Those books reflected two facets of Shafer. A graduate of Yale University in 1934 and Columbia Law School in 1937, an adjunct professor at Pepperdine School of Law, a reader of two books a week, he was nobody’s fool. At the same time, he was a joke-teller and an on-the-bench wisecracker.

But his humor was of a good-natured sort, never derisive. Kindness was his hallmark.

At a time when California Rules of Court, rule 980 absolutely banned news cameras in courtrooms, he declared the rule unconstitutional—a ruling that facilitated efforts to get the rule changed. At a time when a canon of ethics precluded a judge from making an endorsement in a judicial race, Shafer defied it, declining to bow to an invalid restraint on his speech.

Shafer was the antonym of stuffy. He was a man you couldn’t help but like. I did from the time I met him 35 years ago.

I was editor of the Los Angeles Enterprise, a weekly newspaper, now merged into the Metropolitan News-Enterprise. Then a member of the Compton Municipal Court, Shafer was a candidate in a run-off with a Los Angeles Municipal Court judge, Charles Hughes, for a Superior Court open seat. I telephoned him for some comments. We hit it off so well that I suggested, brashly, that he and Hughes come for dinner with my wife and me, to be followed by a joint interview. He was amenable; so was Hughes. The two judges came to our Inglewood apartment, had dinner seated at our dining room table (a card table covered with a table cloth), then sat on our couch and conversed amicably as I took notes.

That typified Shafer’s humility. I did not come to know Hughes well, but certainly his subjecting himself to an interview under those circumstances reflected an unpretentiousness on his part, as well.

Hughes won. Graciously, he acknowledged after the election that his name—reminiscent of that of a chief justice of the United States, Charles Evans Hughes—had been a factor, and that Shafer “does have the ability to handle any court to which he may ascend.”

![]()

Shafer threw a party. While victory parties are routine, I have never known anyone else to stage a defeat party. It took place in Long Beach on Jan. 31, 1971, funded by his $3,000 campaign surplus.

All six of Shafer’s rivals in the primary attended and got up on the stage, joining in singing “I’m Just Wild About Harry”—with new lyrics drafted by Shafer.

|

|

|

The following year, my wife, Jo-Ann, wrote a feature on Shafer for the Christian Science Monitor. It dealt with his “junior jury” program. Shafer had high school students come in and would tell them about the legal system. Jo-Ann quoted him as saying to the youngsters:

“Now, here’s where you get into the action. You’re going to hear a case, have to go out and decide it, just like a regular jury. Call it as you see it. Your decision won’t be final. I’ll already have made mine and written it down. But you’ll get to know what I go through.”

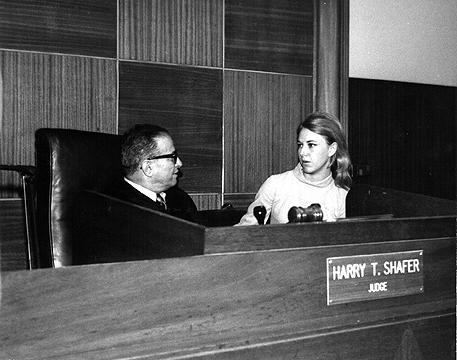

Jo-Ann viewed the proceedings from the bench. Shafer had allowed other reporters to sit there to get a “judge’s eyeview.” Here’s a shot I took of Shafer and Jo-Ann in 1972 (in violation of Rule 980):

In 1976, Shafer was elevated to the Superior Court by Gov. Jerry Brown. Candid, as always, he told this column shortly after his appointment:

“Judges are overpaid and under worked. Any lawyer works 10 times harder than judges.”

![]()

His support of the First Amendment was constant.

In 1974, Charles H. Older, the Los Angeles Superior Court judge who had jailed Los Angeles Times reporter Bill Farr for refusing to reveal the identity of a confidential news source, drew two election challengers. I was volunteer campaign manager for one of them, Deputy District Attorney Alex Kahanowicz (since deceased, as is Farr). Shafer was incensed at the action of his colleague—and had the daring to sign Kahanowicz’s nominating petition.

This column on Jan. 12, 1977 criticized the then-existing canon which forbade judges from taking sides in judicial races, remarking:

“The canon is unconstitutional…but who has the courage to openly defy it?

“For one: Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Harry T. Shafer.

“If he felt strongly about a particular issue or race, he said, ‘I would have to defy it.’ ”

The next year, he did. In remarks to this newspaper, he said of then-Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Vaino Spencer, who was facing an election challenge:

“She’s a decent, compassionate person who deserves to be reelected. She’s got my support.”

Reminded of the canon, he dismissed it, commenting:

“I feel that she’s a colleague who brings credit to the bench—and why shouldn’t I say that?”

(Spencer has been presiding justice of Div. One of this district’s Court of Appeal since 1980. The canon is long gone.)

It was on Aug. 9, 1978, that Shafer took one giant step for the cause of freedom of the press. That’s when he did what no Superior Court judge had done: declare Rule 980 constitutionally invalid and permit news cameras in the courtroom. This followed a like action by a Municipal Court judge, Gilbert C. Alston of the Pasadena Judicial District (who later joined the Superior Court and is now retired).

![]()

Shafer became a family law judge and sought to lighten the normally tense proceedings in such a court with humor. I referred to him in an Aug. 31, 1981 personality profile in the MetNews as the “the Milton Berle of the Superior Court.” Shafer liked the line and pointed it out to interviewers. It was consequently parroted elsewhere.

A Feb. 22, 1982 Associated Press dispatch began:

“On the day he was scheduled to retire [Feb. 8, 1982], a judge dubbed the ‘Milton Berle of Superior Court’ began presiding over the Farrah Fawcett-Lee Majors divorce and the $3 billion property suit of an Arab sheik’s wife. [¶] “Superior Court Judge Harry T. Shafer decided to stay on the bench a while longer. Those were his kind of cases.”

The writer added: “In spite of his levity, colleagues praise his fairness and energy.”

An article in the July 6, 1982 issue of The Globe, a supermarket weekly, said:

“Shafer earned his nickname as ‘the Milton Berle of the Superior Court’ with wisecracks like: ‘Alimony is the bounty after the mutiny.’ [¶] ‘Divorce is a constitutional question of life, liberty, and the happiness of pursuit.’ [¶] ‘In divorce, as in war, truth is the first casualty.’ ”

Shafer was quoted in news accounts distributed around the globe as quipping, “I have gavel, will travel.” He uttered that at a Feb. 16, 1982 proceeding at which he dissolved the marriage of actors Fawcett and Majors. Shafer wanted to travel to the couple’s mansion to look at it up close before deciding on the division of assets.

Majors had insisted the house was his; he made the down payment prior to the marriage and held title in his name, alone. However, the couple jointly plunked $1.5 million into enlarging the home from 5,000 to 10,000 square feet. “That’s not just an improvement, that’s a whole new house,” the jurist said at the Feb. 16 hearing, finding it was community property.

Humorous lines were, of course, uttered in many courtrooms. Shafer gathered recitations of many of them, sticking them in a book he co-authored, “The Howls of Justice.” For example, there was this dialogue supplied by lawyer Paul Caruso (since deceased):

“In the resolution of a divorce proceeding, the judge said to the husband: ‘I’m awarding your wife five hundred dollars per month.’ [¶] To which the husband responded: ‘That’s very good of you, Judge. I’ll throw in two hundred myself.’ ”

![]()

When Shafer on Jan. 29, 1982 announced his initially projected Feb. 8 retirement date, the Superior Court’s assistant presiding judge, Harry Peetris (later presiding judge, now retired), said of him:

“He’s one of our stronger judges for two reasons.

“One is his knowledge of the law.

“But more important is his knowledge of human beings. He can instantly size up and evaluate people, what makes them tick and what makes them act.”

Shafer left the court only a few weeks later than he had initially planned. On the “Click!” page from this newspaper on March 12, 1982 were photos from the retirement party Jo-Ann and I held at our home (a house replete with a wood dining room table) and at a “surprise” (cough-cough) retirement party at the Friar’s Club.

In looking at that page as I write this, I can’t help but notice how many of those who were pictured are no longer alive.

Taken at our home was a shot of Shafer giving his wife, Ruth, a hug. A shot at the Friar’s Club shows them kissing. In the folder from our file cabinet are two photos of them kissing, one a relatively recent picture. Harry and Ruth Shafer were wed on Nov. 2, 1940, and after nearly 65 years, remained deeply devoted to each other.

Loyalty was a trait of Harry T. Shafer, his loyalty to family being uppermost.

A Democrat, his loyalty to his party was such that he always voted a straight party ticket. “Maybe it’s silly, but I do,” he said once in an interview. (I don’t know why it was, but as a Republican, I never felt at odds with him.)

Devoted to his religion, he was active in various Jewish organizations to which he lent generous financial support.

And he was loyal to his friends. I can attest to that.

![]()

The last time I saw him was in January of last year. It was at the reception following the funeral mass for Ed DiLoreto, his former business associate. He, DiLoreto, and the late Court of Appeal Justice Vincent Dalsimer bought Orange University School of Law in 1967, with Shafer serving as president of it. It’s now the law school at Pepperdine.

His funeral is today at noon in Long Beach.

Harry Shafer—that good-natured, irrepressible wag who loved people and was loved in return—is gone. To the many who knew him, memories of him will be warm.

Copyright 2005, Metropolitan News Company